Imagine you had a remote control for your conscious experience of the world, and whenever you wanted to feel uplifted, think faster, relax more, experience joy, empathise with someone, enjoy more confidence, or be instantly less bored, all you had to do was push a button, and the desired state would reliably and instantly arrive to replace your current one. Click.

In this world, when you were sad, you would press a button. Bored? Press a button. You wouldn’t have to do laborious things like practice your speech in front of the mirror for weeks on in order to slowly build-up the native confidence to perform it in public. No, you’d press a button. You wouldn’t have to research areas of interest or pursue new hobbies for years to slowly alleviate the boredom inherent in monotonous and unproductive spare time. Nope. Just press a button. You wouldn’t have to go through a long, unwieldy session of therapy to slowly learn to fully empathise with and forgive your family, boss, or partner. How old-fashioned. Instead, why not pick up your Consciousness Remote Control, press a button, and simply change the channel of your conscious experience instantly? Click.

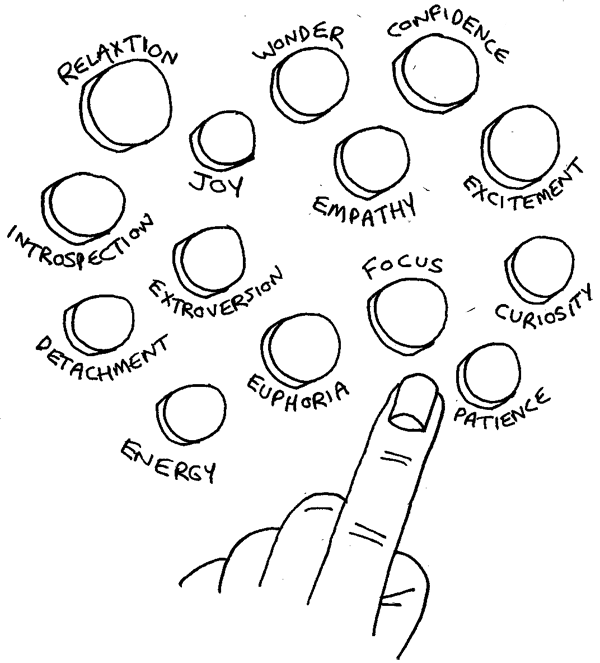

Here are some of the buttons I would expect any top-of-the-range Consciousness Remote Control to have:

Well, luckily we don’t have to work too hard to imagine a Consciousness Remote Control, because we already live in a world where almost precisely such a remote control exists.

We call them drugs.

Saying positive things about ‘drugs’ is risky. It’s a baggage-laden collective noun for good reason, and it’s not hard to see why slightly more hysterical people might get emotional when discussing an umbrella term for things as diverse in their effects as coffee and LSD, beer and barbiturates, cigarettes and crack cocaine, magic mushrooms and morphine. However, there’s one predominant quality of all ‘drugs’ that is not at all controversial: drugs consist of stuff – powders, liquids, crystals, gases, beans, leaves, cacti, fungi, rotting fruit – that contain chemical compounds (look for the scrabble letters LSD, THC, DMT, MDMA, etc.), which can be absorbed by our mammalian bodies, whoosh through our bloodstreams, nip across the blood-brain barrier, and plug into receptors in our brains, that are – rather remarkably – exactly the right shape to take them. Then something pretty weird happens.

They change the experience of whatever part of life is currently screening in the theater of our consciousness.

CLICK.

Drugs are, quite literally, mind-altering substances. They are psychoactive catalysts (or gateways) to different states of consciousness – many of them so decidedly interesting, pleasant, uplifting, helpful or just generally appealing to try out that ‘we’ (society/voters/the government/whatever) make most of them illegal, so democratically afraid are we of dependency, addiction, and the other risks we perceive to civilisation of too many people having too nice a time on their own, instead of doing all the other things they’re supposed to. Comedian Louis C.K. put it this way:

I don’t know how I’m going to tell my kids [about drugs] … How do you take a miserable person with no control over their lives, and tell them with a straight face: ‘you can’t do drugs … You can’t do it, baby… All drugs are are a perfect solution to every problem you have right now.’ How do you beat that?! Drugs are so fucking good… that they will ruin your life! That’s how good they are!

Think about it this way: your waking life feels like an experience (rather than a something which is having an experience), because you only experience life from one perspective – a kind of ‘headless’ vantage point as the consciousness ‘you’ are. Hopefully, it’s a mostly good experience. If ‘you’ are indistinguishable from your thoughts, feelings, and experiences funneling through your head, then what drugs are actually doing is temporarily changing who you are. (This should be our first clue as to why some people crave them, some people can easily dip in and out, and some people are terrified, perhaps rightly, to never go near them.)

In terms of the absolutely reliable consciousness changes that drugs bring about, drug dabblers, drug aficionados and drug addicts will find it increasingly easy to pair up many of the desired states listed on the Consciousness Remote Control with their corresponding chemical partners. Some of these conscious states are relatively mundane and familiar (drunk, over-caffeinated), some of them are harder to define (high, stoned), and some of them sit so far outside the parameters of normal conscious experience, they feel less like you’re changing the channel of your experience, and more like you’re downloading an IMAX experience onto your wind-up radio (tripping.)

For our purposes, however, we will work with the most commonly-used drug on the planet, because it is the one that the majority of readers are most likely to be familiar with: the chemical C2H6O, a.k.a. the active chemical compound in fermented organic sludge water, a.k.a. the selection of popular liquids more lovingly known as booze.

If you’re feeling shy at a party, or worried on a first date, or struggling to make conversation at an awkward family dinner, what you might be looking for is this button:

(Can’t find it? It might also be labelled extroversion, bravado, lowered inhibition, or reduced self-consciousness.) Luckily, the button is there on most of our Consciousness Remote Controls, labelled beer or gin or whiskey, and you can press it from basically anywhere you want in our modern world of near omnipotent booze-access — from shops to airplanes, from hotel mini-bars to almost every public building that you’re expected to spend more than an hour in. Click, click, glug, glug.

Your increasingly confident State of Consciousness is on its way!

“OK,” you say, “great! Finally, the solution to all life’s annoying problems! Let’s all do all drugs all the time!”

Ah. Well, this is awkward. You see, there’s a second way to imagine our Consciousness Remote Control.

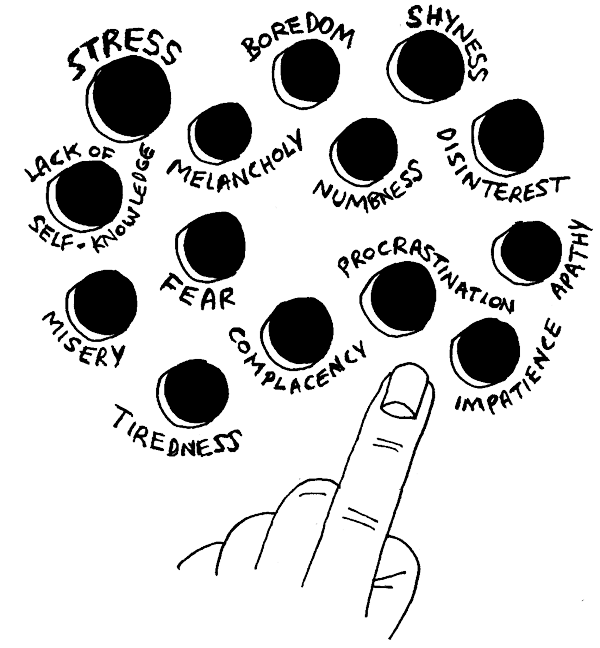

Firstly, let’s just take those buttons off. Instead of the State of Consciousness we want to come, we can now see the State of Consciousness we want to get rid of. OK. Now the holes represent the baseline ‘problem’ we are actually trying to solve by using the drug in the first place. Here’s our exact same Consciousness Remote Control, except now the device looks about as much fun as Morrissey’s to-do list:

From this angle, the story of drugs already looks a little different. Indeed, this Consciousness Remote Control looks less like a snazzy tool-kit for all kinds of positively-tweaked experiences and other casual wizardry, but more like something designed by the Massively Depressing Television Company.

Actually, looking at some of those fairly big and recurrent problems, drugs look a bit more like something else…

There’s two main ideas about drug addiction, which you can see in action watching the (conservative) journalist Peter Hitchens bicker with Chandler.

In summary: Peter thinks that addiction is a choice, and a not very good choice, and a not very good choice that the government should protect us from with its friendly police-type people. Chandler thinks it is not a choice, at all, but a medical condition, and as such the government should protect us from it with its friendly doctor-type people.

The debate is politically charged, for two reasons: Firstly, the Addiction-as-Not-a-Very-Good-Choice model fits more with ideologies on the right of the political spectrum, with its emphasis on personal freedom, and therefore personal responsibility, and less with the left, with its emphasis on trying to design into society systems that account for the world’s inherent unfairness, and, therefore, collective responsibility for its problems, ‘addiction’ being one of them. Secondly, if the Addiction-as-Disease model is right, that’s a bit awkward, given the rather embarrassing little fact that for a hundred years we’ve been shepherding hundreds of millions of people into prison to punish them for being so unhelpfully unfortunate. Oh.

On top of that, not only could people like Peter Hitchens no longer feel quite as delighted with themselves for being Very-Good-Choice People, but suddenly The War on Drugs would seem a lot more like an expensive global witch-hunt for the mentally ill. This would be, to say the least, embarrassing. Meanwhile, we’ve made drugs (which people wanted/needed) harder to get, therefore more profitable (criminals are famed for understanding supply and demand), and our world spectacularly less pleasant (criminals are less famed for their responsible business practices.)

Well, in this instance, I’m with Chandler and friends.

Is addiction a disease? These fairly big-hitters think so:

(There is still some controversy about labelling addiction as a full-on ‘disease’ alongside more obvious body malfunctions like rickets, leprosy and scurvy, which no amount of ‘will-power’ could overcome. While, in general, the definition holds in the sense that we know problematic, physical changes have occurred in an addict’s brain – changes which can be undone, but slowly – some doctors are reluctant to define personal responsibility completely out of the equation, wanting to avoid self-fulfilling ‘victim mentality,’ or transfering all responsibility away from Chandler when it hasn’t been his day, his week, his month, or even his year.)

Regarding governments’ acknowledgement of the well-prescribed medical consensus, however, I think most states are still acting like toddlers with chocolate all over their mouths. Mummy Scientist and Daddy Doctor are asking politely what’s going on, yet politicians keep claiming over and over again that the entire cake is gone because it was stolen by a dinosaur.

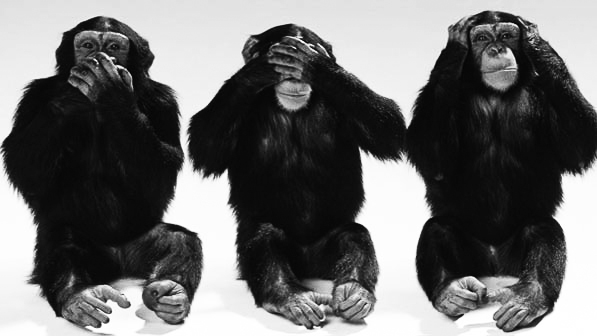

No. A hundred years of ‘Drugs are Evil‘ and ‘Just Say No!’ and Idiots have muddied our understanding of drugs, I think, to the point where we don’t understand what is happening to people who become addicted to them, so we don’t sympathise with them easily, so we don’t really want to (or know how to) help them. It seems to me that most of the world’s current drug policy is this:

1.) Addicts are shit.

2.) We don’t want addicts.

3.) Drugs create addicts, so no one should take drugs.

In other words, we’ve assumed that something inherent to the pharmacology of the chemical is hacking otherwise sensible folk that could be behaving themselves and paying taxes. By this theory, if you take heroin for a week, that chemical will set its grubby claws into your squeaky-clean brain, creating a new ‘equilibrium’ that only more drugs can maintain. Heroin has climbed into the driving seat, and now it, instead of you, is in control of the vehicle. You’re an addict now, kid. (Please proceed to prison, you naughty little drug person.)

But this idea has been so thoroughly murdered in medical, scientific and academic circles that whenever we see a journalist or politician trying to give it CPR in public, we should regard them with the same level of worry as a figure skater shouting, “The world is the shape of a pickle! The Jews did 9/11!”

It is little more than an unfriendly relic of Victorian daftness, unhelpfully enshrined in our legislature, from a generally more silly time when we had a lot less scientific understanding of the body, brain, and everything.

It was basically guesswork

Knowing nothing about the inside of the brain or how it works, we had to pin a wild stab-in-the-dark Theory of Addiction on weak character, moral failure, and general tomfoolery of the Pete Doherty variety.

Aw, so nice that you care. Pete’s doing better, thanks. While researching this article, I learned that he’s out and about, thanks to an Abstinence-based recovery program. Here’s a quote from the man, more famous for stumbling around near bins, looking like a schoolboy that just lost a fight with a quarry: “I suppose there’s a difference to being attracted to trinkets, rituals, and the idea of spirituality—which I think I am—and actually being engaged on a daily level with amending spirit faults when for me it’s been hard giving up everything else. There’s an element of mindfulness, which I believe is taken from the Buddhist culture. I don’t like to say it, but fuck it I will: it’s just the essence of Being really. And not getting on the train—not going with the negative thoughts.” Fine.

This fundamental confusion has led to a misdiagnosis of what society’s actual ‘problem’ is:

We’ve said: Drugs are addictive. Otherwise people are, or would be, fine. So, let’s fight the drugs (maybe even have a nice, expensive, world-wide War on Them.)

We should have said, though: People get addicted. Drugs are a thing that people that get addicted get addicted to. How do we fight addiction? Oh look it’s a massive pain in the arse project that involves reformatting a lot of society, one addict at a time. Annoying.

Just as an addict’s first step to recovery is to admit they have a problem, so too can society only recover when it looks in the mirror, and recognises the unpleasant things it has done to itself.

We do not have to visit a madhouse to find disordered minds; our planet is the mental institution of the universe.― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Addiction is easiest to understand when you realise that every person has some problems, some neuroses, and some damage, lightly-hidden behind their eyes. We are all a bit broken, bless us. We just can’t easily see the health issues in each other’s heads.

Indeed, it seems basically impossible, or exceedingly rare, for someone to be thrown into the world, swim through a family, a school, a culture, and a puberty of infinite possibility for cruelty, then emerge as an adult totally dry on the other side. Nuh-uh. The odds are stacked extraordinarily against any of us coming out of something as insane as a childhood as a fully, totally ‘normal’ human being, completely well-adjusted in every respect to a very weird world (if such a thing were even possible.) Instead, we develop our odd little human problems, bundled up into a semi-functional personality.

However, let’s face it, we definitely don’t all get an equal share of the potential damage that’s getting doled out. Parenting is a game that has novices, rookies, pros, and people who probably shouldn’t even be allowed to play. Let’s briefly imagine a spectrum, with Joseph Fritzl and his wife-daughter-combo on one end, and Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie on the other. You were born to parents somewhere on that parenting continuum. No one gets to choose their parents, their bodies, their gender, their sexuality, their DNA. It’s all the luck of the draw, life’s most significant and indifferent lottery, and we all only get the one hand we’ve been dealt.

Welcome to Earth, kid. Good luck.

It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that a quick glance at the wider world reveals that some people are really hogging more than their faire share of society’s problems. Addiction is easiest to understand when you make the simple connection that drugs just happen to be an instant, reliable, but temporary, answer to many of them.

If you’ve escaped with relatively ‘lesser’ problems – let’s say, you only feel 92.6% as funny as your funniest possible self until you’ve had two pints of beer – then the level of risk you’ll face in relation to alcoholism is massively lower than someone who was abused as a child, grew up with rubbish parents, or is regularly brain-bothered by some other brand of trauma, who finds (perhaps unknowingly) that alcohol offers some relief from the every day problems inherent to being sober. If alcohol is the same solution to both problems, it’s easy to see in which scenario it has a much more urgent purpose as a psychological crutch. If the baseline problem is always simmering in the background or reoccurring regularly, the allure of the Remote Control will be strong.

If we imagined these two problems as purely medical problems – like the commonly-held medical classification suggests we could – we notice immediately that one of these hypothetical patients needs their medication more than the other. ‘Psychological pain,’ while it might sound like the kind of thing you could simple shout ‘man up!’ at as you drive past it in a van, is no trivial matter. Some fMRI research suggests that brains might well be registering ’emotional pain’ in similar ways and regions as ‘physical pain’ [1]. This shouldn’t actually surprise us: the need ‘to belong,’ for example, has the exact same evolutionary imperatives as the Darwinian drives for food, sex, and shelter. In-group tribal cohesion meant, for an evolutionary amount of time, survival. It makes sense, then, that a failure to meet this ‘need’ could make our bodies ‘feel’ as physically uncomfortable as hunger does. Rejection, loneliness, social ostracism, or lack of meaningful connection to ‘our tribe’ hurt. We are ‘hungry’ for ‘a reward’ that a hundred million years of natural selection have hard-coded us to be hungry for.

The alcoholic is suffering, and some clumsy brand of cheap relief is available to him or her at every tavern in town.

From a medical point of view, drugs, alcohol and any other escapist compulsions generally remain pretty un-ideal forms of self-help for psychological problems, since they are treating symptoms, not preventing them. To psychologists, they’re numbing the pain of the toothache, but ignoring the rotten tooth. Our alcoholic treats the pain, but then the anaesthetic wears off, to be replaced by a hangover. As the same-old problems come back, so must the solution – the alcoholic re-doses. Click, click, click. The actual character of their sober life is the problem they are trying to solve — and so the alcohol will remain a necessary crutch unless/until that life somehow improves. If our hapless self-medicating drunk accidentally stumbled in to a therapist’s office or a healthy relationship or a more rewarding job or a yoga class or a dojo instead of the pub, pub, pub, it’s not hard to imagine that some competing desires might start – at last – to win out.

In the meantime, though, for the lowly price of five bucks a hit, one can fix him or herself for the night.

I have a friend who gets really strong period pains, which she’d be delighted to know I’m writing about on the internet. Once a month, she faces the following choice, which she has and might well face for a total of 30 boring menstrual woman years: she either loses 3-5 days per month – workdays, weekends, her period doesn’t bloody care – to mood-destroying, leg-bothering and generally day-ruining crampy bullshit; or, alternatively, she can find the strongest dose of a drug (Ibuprofen) that she can legally get her hands on, push that button like she’s popping Tic-Tacs, and get on with the good life without her daft womb deciding now must be horrible lonely sofa week.

Now, imagine I, as either a person with a more reasonable womb or a non-womb-owning member of the same species, told her this: “You take drugs too much! You’re just masking the pain! You should listen to your body. Don’t cover it up; go through it, feel all of it, it’s trying to tell you something for a reason, man. Don’t you know that Ibuprofen is bad for your kidneys?”

“Um, shut up,” I think, would be a perfectly reasonable response.

I share with you my friend’s period drama (ho ho ho), only because I think in her situation those shitty days are absolutely unnecessary. They are pointless, meaningless, and, in a modern world where God is Dead but 800mg Ibuprofen mega-tablets are alive and kicking, avoidable suffering (you might argue that their ‘purpose’ is to prepare her body for childbirth, you contrarian you, but this level of pain can’t be necessary, otherwise all women would suffer similarly. My friend’s body, in particular, is not a team-player.) The kidney argument might be valid, but it certainly looks like a proportionate risk/reward trade-off, given the overriding pain-in-the-thighs bullshit she would otherwise have to endure because of some random, annoying, unfairly inherited expression of her particular biology.

If you can understand why someone would Press the Pain-killer Button to alleviate the Period Pain Problem (or any other recurring physical ailment), then why not also for the emotional pain of the brain? This is the more compassionate view of drugs we could foster: sure, it’s better not to need medicine… but if someone does need it, who are we to take it from them?

Here are some words which have caused us an unending amount of trouble since we got cocky enough as an upright animal to try and add our cute little human meaning-labels to them:

To try and explain any of them seriously or coherently is to risk sounding like a maniac, especially in scientific terms, and even the most intense theological or philosophical writings about these clumsy words often straddle a fine line between things that sound true to things that sound so vague as to be almost meaningless. To one person, three words like “God is Everything” sound like the spiritual key to the cosmos. To another person, perhaps sitting too close to the first person on a night-bus, “God is Everything” is the kind of simple gibberish that inspires an urgent change of seats, just in case it’s followed by a touchy-feely invitation to “the magic love forest of Gaia” or an ominous-sounding shed.

For the best/worst example, look no further than Martin Heidegger, the man who one day decided to uproot 2,000 years of philosophy by noting that all of it, every single word of it since Plato, “has attended to all the beings that can be found in the world (including the world itself), but has forgotten to ask what Being itself is” (1). This pain-in-the-arse idea he called Dasein (‘There-Being’.) Here is a dense and boring quote from a summary of the 20th Century philosopher for a lovely example of how trying to say ‘true things’ about ‘profound things’ quickly produces sentences that could just as easily appear upside-down on the walls of an insane asylum in crayon:

Heidegger turns our focus away from the philosopher’s fixation on the thinking ego, towards the consciousness of Being. His attention is on what is not thought, on what is forgotten by Dasein in its thereness as a human entity. He wishes us to resight ourselves on the situation itself of being-there, as we are, at a loss in the obliviousness of everyday life. Only then can we recognise our deep fall into the inauthenticity of one-sided technological development. The risk of falling into inauthenticity occurs when the particular Dasein, which is the public ‘they’, or as Heidegger puts it, to the everyday self of Dasein, which is the public they-self.– Richard Appignanesi, ‘What Do Existentialists Believe?’

Ahem. OK. Taxi!

Remember, too, that that is from a summary of Heidegger. Dealing with the actual 438-page work Sein und Zeit (‘Being and Time’) is like trying to swim through a soup made of wood with your eyes. Delve into it if you don’t mind gambling with your sanity, and see for yourself whether you can differentiate between sentences of profound, ultimate truth, and sentences that you might otherwise expect to hear from a bearded, mad-eyed man emerging from a bin.

Well, what people like Heidegger – and every other relevant philosopher, theologian, guru, priest, spiritualist, and 4am drug-addled loony in a drum circle – are essentially going to such great, murky depths to interrogate is this: there’s an uncanny thing to notice about your/our situation in the world, that is so incredibly, incredibly, incredibly, incredibly, incredibly, incredibly weird, that perhaps the only bigger miracle than it is how you (and I and everyone) get anything done in its presence:

It’s that you/we are conscious.

If you thought ‘duh, of course I am, God did it, so what, shut up’, then there’s a good chance this article is not going to be for you. That’s ok, and I hope you have a lovely time wherever you end up next (I suggest here.) If you thought, however, something more like ‘I know, man! It’s soooo trippy! What the fuck is going on?!!?!?’, I like you. You stick with me for the next lump of your confused, enthusiastic little life, and we’ll go on a little journey into the deep heart of nothing and everything. Strap in.

So. Everything you hear and see and think and feel and recognise and remember occurs in the non-spatial, non-material, boundary-less theatre of your consciousness. Obviously. It is the base ‘fact’ at the root of your experience of everything; the canvas upon which your world, the world around you, is painted. Everything ‘out there’ exists – it seems – on the precondition of your being conscious to experience it. When you are not conscious – in the year 1416, for example, or when you are taking a nap/deceased – you have literally nothing to report back about reality. There is not even a reporter that could be doing the reporting.

You exist now, and, unlike basically everything else that exists, you are also aware of this existence. In a universe of atoms and quarks and photons and rock and gas and dust and brains and potatoes – ‘you’ – whatever that is – are a subjective experiencer of apparently physical, apparently material phenomena; weirdly, obviously, made up of all the same stuff that a universe might contain, yet able to ask that universe what a universe is.

You do all this in the inner abstract world you know yourself to have, the one that is currently being fed by the inputs of your bodily senses. It’s a kind of formless ‘awareness,’ locked on to a heavy reality trip, yet simultaneously capable of the limitless abstractions of thoughts, ideas, and conceptualising as yet ‘non-existent’ things, like sophisticated new jokes about your colour-blind friends.

You are always experiencing everything in this entirely private realm of your own consciousness; incommunicable and totally unprovable to any one else, just as theirs are to you. Furthermore, this consciousness generates your feeling that you are a self – whatever that is – an outwards-facing, identity-shaped lens upon the universe, staring out at it, and/or sucking it back into the space behind your eyes, where you – whatever that is – er, is.

This is all weird.

However, upon further inspection, it even seems a bit controversial to say that you HAVE a consciousness – the way you might have knees, a spatula, or an expensive coastal property you’ve hornswoggled from a dementia-ridden spinster – you, instead, kind of, ARE a consciousness. Point at your face. What are you pointing at? There’s no-thing there, where ‘you’ are supposed to be. Try it. Please. Now.

The no-thing

The philosopher D. E. Harding gave a nice, funny instruction to noticing this predominant feature of consciousness in his book, On Not Having a Head:

The best day of my life – my rebirthday, so to speak – was when I found I had no head. This is not a literary gambit, a witticism designed to arouse interest at any cost. I mean it in all seriousness: I have no head. It was about eighteen years ago, when I was thirty-three, that I made the discovery … To look was enough. And what I found was khaki trouser legs terminating downwards in a pair of brown shoes, khaki sleeves terminating sideways in a pair of pink hands, and a khaki shirtfront terminating upwards in – absolutely nothing whatever! Certainly not in a head … It took me no time at all to notice this nothing, this hole where a head should have been, was no ordinary vacancy, no mere nothing. On the contrary, it was a nothing that found room for everything—room for grass, trees, shadowy distant hills, and far beyond them snow-peaks like a row of angular clouds riding the blue sky. I had lost a head and gained a world … Somehow or other I had vaguely thought of myself as inhabiting this house which is my body, and looking out through its two round windows at the world. Now I find it isn’t really like that at all. As I gaze into the distance, what is there at this moment to tell me how many eyes I have here – two, or three, or hundreds, or none? In fact, only one window appears on this side of my façade, and that is wide open and frameless, with nobody looking out of it. It is always the other fellow who has eyes and a face to frame them; never this one.

It’s a profound thing to notice, yet it is ever there to notice.

To be something; and to know it; and to experience things as an open lens upon existence – is freaky beyond mere words. Indeed, in the 1989 Macmillan Dictionary of Psychology, a book which sounds like not the absolute worst place to go to if you wanted to understand a word relating to the mind, Stuart Sutherland said this of ‘consciousness’:

The term is impossible to define except in terms that are unintelligible without a grasp of what consciousness means […] It is impossible to specify what it is, what it does, or why it has evolved. Nothing worth reading has been written on it.

Oh, ok.

Essentially, according to Mr Sutherland, we should all be wide-eyed, gob-smacked, flabbergasted, freaked-out, awe-struck, dumb-founded, stupefied, spell-bound, and unendingly astonished in a perpetual hypnotic tsunami of speechless wonder at this thing; this experience; this verb that we are called being… except then we probably wouldn’t get anything done. And things need to get done, otherwise we wouldn’t have any cheese.

So, what do we do instead, when faced with the infinite, unparalleled mindfuck of our situation?

Well, we think.

We think, it turns out, quite a lot. We’re chatting, joking, busy, lost in thought, learning something, absorbed in a book, a movie, The News, an activity, a game, work, we’re remembering, misremembering, reliving past arguments, rehearsing future ones, fantasising, fictionalising, talking to ourselves, others, pets, postmen, thinking about ageing, memories, goals, grocery lists, evening plans, about our mistakes, about dinner, about ISIS. We mostly – and seemingly automatically – let our consciousness wander throughout the day in all kinds of weird and wonderful directions, everywhere and anywhere, it seems, except inwards, at itself.

This, it turns out, is not ideal. Yet it is simultaneously not that easy to stop.

Now, I used to be very suspicious of the word ‘meditation,’ because it sounded an awful lot to my dumb, young ears like sitting alone and being quiet, two proposed experiences that a lifetime of running around yapping made me distrust immensely. The word ‘meditation,’ in my stupid-head-dictionary, conjured up thoughts far, far away from ‘normal, ordinary people like me,’ yet much closer to ‘new age nonsense hippy-dippy beard homoeopath guru weird bald monk burn-themselves people over there.’ To me, it’s four innocent syllables swam in a prejudice soup of unscientific, religious, “spiritual,” and, most importantly, boring-sounding ideas, that had no sort of relevance to a modern man of beer and science like myself.

“‘Meditation,’ you say? Hm. I’ll pass, thanks.”

Then I read some stuff about it, and, to my surprise, it turns out that ‘meditation’ is basically a synonym for ‘occasionally listening to the mental, incessant jabbering going on inside your mad fucking head.’

Which is fine, isn’t it?

So, cross your legs, get comfortable, close your eyes, whisper loving thoughts to the crystals on your Shamanic dream-catcher, and listen, just for a minute, to the mental, incessant jabbering going on inside your mad fucking head. Try first, for even ten seconds, not to think, and pay close attention to what happens. Here’s a space to help:

Did you do it? Of course not. Well, if you had, what you would have instantly noticed is that the circus is permanently in town, they’ve raided the liquor cabinet, and are now holding your mind-voice hostage. In other words, ‘not thinking’ is freakishly, frighteningly not possible. You can’t turn the damned internal voice off, so intent is it on it’s own selfish agenda of non-stop nonsense. Blah blah blah, it goes, all day long, like the Kanye West of your own head.

Meditation, at its humblest, is simply a way to notice, however temporarily, that there is a weird, distracting, and hypnotic automaticity to the thoughts overlaid on our conscious experience of the world. Here’s another space, for you to notice the next word which pops into your head. It can be anything. OK, any word, go!

What did you think of? I bet it was weird, you freak. Could you possibly explain why it was that word – not any other possible word – that came up? Did it, in fact, feel more like you were the receiver of that word; the satellite dish that caught its signal, rather than the workshop in which some rational actor inside you carved it? Presumably it somehow bubbled up from the froffing, formless, infinitely unknowable, inaccessible, neuro-chemical purgatory of your subconscious, yet we might as well say it was beamed in by space fairies, downloaded from the god-mind, remembered through a past life echo, or telepathically inserted by the Flying Spaghetti Monster on the other side of Saturn, for all the evidence that your conscious mind can muster that your subconscious is a thing that exists. Its harder still to pinpoint how you chose it. Whatever the answer, it’s useful to notice this spooky lack of authorship we seem to have over the content bumbling, staggering and meandering through the most personal and private realm of our minds.

“I’ll think of something.”

On top of that, there are our feelings – those wordless thoughts that we feel in our bodies (literally, our veins pulse, stomachs churn, cheeks blush, throats throb, fists clench, eyes leak, etc.). If you’re on auto-pilot day-dream mode, your emotions can be pretty effectively overridden and puppeteered by whatever the great frothing, stress-catering chaos of existence is going to throw at you next. Your mood could be great, then the universe drops a tree on your legs. Ow. You could be feeling awful about your ruined knees, then a lemur jumps into your pocket. What a world. You can wake up on “the right” or “the wrong side of the bed,” or have a sudden, total mood switch instantly triggered by an abstract thought or memory that pop up from nowhere. Feelings happen to us. They often seem to roll in and out of our conscious landscape, colouring the experiences we have like weather. This is a nice and healthy way to imagine them, I think, especially should you need to find some sunny solace in the darkest peaks of winter. Sometimes, feelings simply come and go – patches of cloud and ‘shine – and we need only wait for them to pass.

In other words, then, we don’t seem to be a conductor, directing an orchestra of sensible information and logical instructions to ourselves. We are more like infants, left alone for the day in front of a YouTube playlist for the search term ‘Japan.’

What’s more, this is happening all day.

Indeed, we’re thinking so much, about so much, that we’re basically day-dreaming every moment that we are awake. We are accidentally, unconsciously ignoring the sum worth of The Freakiness, fretting instead on its hundred thousand annoying little mundane components (bills, work, gossip, etc.)

And what are we thinking, exactly? Or, if really want to get into it, why are we thinking at all? Is it really so normal? That sounds kind of weird, but definitely no weirder than it is. When I think, “I want cheese”, who is the intended audience of this information? Well —me— right? But, surely I already know I want cheese, otherwise I wouldn’t think it… right? Or am I the intended audience of this thought? Am I somehow the one being told; the one learning “I want cheese”; the radio receiving the cheesy signal? If so, then, who or what or which process is authoring this thought?

There seems to be an ongoing conversation in our heads, if that’s where we are, yet there’s surely no one in our heads but ourselves to have that conversation with.

There’s a good, or at least convincing, theory on why we’re talking to ourselves all day, inside our own heads, engaged in a behaviour that would seem outwardly insane if it could be broadcast on loud speakers from our ears to a cafe full of people impressively drinking espressos.

But first, it’s helpful to note that we probably wouldn’t be monologuing to no-one like the mad old Shakespeare of our own minds, if we had not been born in our current, talky-talky modern human context, but instead in the middle of a jungle, estranged from civilisation, raised by a tribe of friendly, mischievous baboons. It should be obvious that in our alternative naughty baboon lives, we would be free of all language-based thought, and our inner worlds would not – could not – be governed by ceaseless linguistic self-chattering, but, perhaps, more by nature’s noise, the leafy sounds of the jungle around us, primal, mystic fears of faceless, shapeless unknowns, and other general baboonery.

Thoughts?

The human civilisation context, however, is uniquely different.

When we are babies, we possess – presumably – some level of consciousness. By which I mean, there is presumably something it is like to be a baby. But conscious is probably just about all we are, so far – indeed, it might just be the purest form of consciousness in some ways, since it is yet untouched, unhurried and undivided by anything so troublesome as an idea, concept, symbol, or bias. No words exist, so no definitions exist to separate anything from anything else. But this state of primordial, pooing-ourselves awareness doesn’t last long, because all the live-long day our parents our blabbering at us; grandparents, too, are making funny, lip-slappy face-noises in our direction; friends, family, strangers, postmen, televisions, radios, all waffling nonsensically in our direction, like mysterious mouth-instruments. We’re encased in an aura of near constant human noise.

Then, after a while, we start to notice patterns in the noise. That meaningless sound –mum– keeps coming up, whenever the creature with boobies that we like so much arrives. Then the meaningless noise –dad– pops up with enough frequency for us to notice that it seems to signal the other one, Mr Useless Bloody No Boobs over there. Before long at all, we’re the fertile soil for a growing vocabulary and grammar, echoing these new sounds back to the world, trying to participate in some mad, desperate attempt to help it understand that we’ve pooed ourselves, or want boobies, or need sleep, or would immediately like for the Red Fire Truck Toy to be in our mouths, please. We want things. We need things. We pick up language, as we would pick up a tool.

All this experimentation, trial and error and copying soon leads us into the world of The Talking; and it’s not long before we’re practising this particularly human brand of communication all day long and everywhere. We become the toddlers, then the young children, wandering around the playground, muttering out loud, monologuing to the world each and every thought that pops in to our heads. Every thought is a word, said out loud, for all to hear. We sound like midget maniacs, but everyone think it’s cute, so we carry on.

big doggy blicenah uhm-na me cup mama go bye-bye he shwahwoooo where doggy where doggy gone? croosh mama doggy bye-bye to the everyday self of Dasein, which is the public they-self.

– Martin Heidegger, age two and a half

Then this out-loud monologuing becomes, well, not so cute. We get older, and older still, and suddenly become increasingly aware that not everyone is just saying everything that they think of immediately, like we are. Adults don’t. Bigger kids don’t either. Our older siblings have stopped. Then our friends – our peer group – stop, one by one, going out like dying stars in a night-sky when something creepy is happening in outer space. The exterior world – and our increasing awareness that we are not free, lone agents, but woven deep into a social fabric that can painfully ostracise us, judge us, tease us, and be mean to us – doesn’t stop our fun, new form of expression entirely, but cautiously pushes our monologuing inwards, to the only place left where it is socially safe from the dangers of the tribe: our consciousness.

The voices of mum and dad, which became our broadcast-out-loud playground voices, become the voices in our heads… where they will stay forevermore, bickering and dictating the moment-by-moment account of our lives, memories and imagination on our own private radio station, Head FM.

And what’s more – we forget this process happened. The day-dream begins.

We can no longer see the voice in our head as a detached and different entity, as it once was, falling from the mouths of others. No, now we identify with it. Suddenly, the voices in our heads stop being just those –voices–in–our–heads – coming in and out, automatically. Instead, they become us. It becomes me. The innocent thought rolls in, “I want cheese,” and suddenly that baby – that free, agenda-less baby absorbing its environment as a pure, unified field of conscious experience – is a cheese-chasing self, deciding itself for the first time as separate to everything else. The baby’s identification with the voice has, clumsily, inadvertently, spawned an ego. Oh dear.

Those that fail in this process – who don’t internalise the voices – become the unsettling people of our world; the muttering, monologuing madfolk we see “talking to themselves” – just as we are – except they’re not following the Unwritten Rules of the Civilisation. They’re Talking to Themselves wrong. We’re doing it right, though, aren’t we? “Yes,” say our egos, those strange and delicate creatures in charge of all of us and everything. “We’re doing it inside our heads, just like we’re supposed to,” we whisper to ourselves.

So there is consciousness – the theatre – and thoughts and feelings – the actors and the orchestra – which play out upon its stage. And there is the full, immersive experience of reality, which you can most easily notice when you try to locate your head, and fail.

And this nothing where your head should be is, well, as the man on the night-bus would say, everything. It’s where the magic happens.

When we close our eyes and put our fingers in our ears, and shut up, it is easy to notice that, behind the input of our sight, behind the input of our hearing, behind the inputs of all our other senses, there is something left. Or, to put it another way: even if you applied a blind-fold, two ear-plugs, local anaesthetic to your whole body, and then floated in an isolation tank until you were not aware of the weight, position or even the sense of having a body, there would not be nothing. Obviously. ‘You’ won’t be gone. Nullify all of your senses, and you won’t nullify the presence of which they are the probing tentacles, groping the external world around you, like the many hands of a reality pervert. Feel free to take a few minutes if you want to confirm this for yourself.

Doo be doo be doo.

Did you? Of course not, you naughty reader.

What this something is, though, remains fundamentally mysterious, and it’s weird that something so fundamental is so mysterious, because, at the same time, this something has the equally weird quality of feeling – subjectively, and with typical human arrogance – like it is the centre of everything – the point at which all things in existence seem to simultaneously begin and end: you.

When we close our eyes, it is easier to be aware that this something, is, kind of, sort of, a bit, well, like a space, and we can further notice too that it doesn’t seem to have any limits, or boundaries, or corners, or edges, or anything that something inside a head – if that’s where it is – should have. And this too is capital letter Weird. Isn’t our head 20cm by 18cm by 13cm, with a 56cm circumference? Wikipedia says so. Isn’t it bone, and gristle, and skin, and brain, and blood, and hair, and a cute, boyish face? My creepy doctor says so.

So, what right does this meat bloody football on my meat bloody neck have containing an infinite bloody space?

![[10] Guy](http://www.hencewise.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/10guy_2.png)

(Not to scale.)

Generally, Russell Brand sounds most like a person you shouldn’t listen to when he’s talking about “god,” but if you ever probe into what he means by “god,” and I did, you don’t actually get a presumptuous and all too familiar account of an exterior rumoured (male) sky personality – the character ‘God’ whose name people shout before they blow themselves up in crowds – but simply this:

What [religions] are trying to do is make sense of our perspective as awake, conscious, sentient beings within the infinite. For me, as a person who believes in god, my understanding of god is this: My consciousness emanates from a perspective, and it passes through endless filters – the subjective filters of the senses – and of my own biography (“this is good, this is bad, this is wrong, I want this, I don’t want that”) – but behind all of that is an awake-ness; an awareness that sees it all […] None of us can know if there is a god, but we can know there is an us.

In other words, he’s not – as it might first seem – endorsing a judging, watching, needy and suspiciously human-like deity that certain things must be done to appease, but what instead amounts to a different, more Eastern, notion of consciousness (god is not ‘out there‘, but ‘in here‘.) At best, Brand’s philosophy is a nice, innocent means of connecting with the profoundness of existence, and, at worst, little more than a fluffy logic circle, that could instead read: “None of us can know there is a god. We can know there is an us. My consciousness emanates from a perspective. I’ve just decided to call this consciousness “god,” to confuse everyone.”

In other words, Rene Descartes’ (who is not a woman at all, it turns out) famous, 400-year-old one-liner, ‘I think, therefore I am.’

We can see, anyway, that some people are using the words consciousness and god, almost interchangeably. Indeed, in light of admitting what we don’t know, all of the tricky words at the beginning of this article start to seem like nothing more than synonyms for consciousness: It’s where reality is happening; It is the something made of nothing; It is the subjective, in which the objective occurs; the no-thing in which all things appear; Having it is existence; Not having it is non-existence (or, as the cool kids sometimes call it, death); If the Big Bang was a tree falling in the woods of infinity, we beings of higher consciousness are the witnesses in the dark cold silent emptiness that know it made a sound.

As Carl Sagan – astronomer, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, and stoner – once said, presumably in an alarming whisper to a fellow passenger at 3am:

We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.

It’s easy to see – when confronted with the full Weirdness of what’s going on – that almost everyone on earth, especially every particularly religious maniac, is grappling with, and arguing over, a different flavour of the same original controversy; and almost all viewpoints, and even ideologies, are stemming from the same source presupposition that we don’t at all understand, however much some philosophers, theologians, gurus, priests, spiritualists, and 4am drug-addled loonies in a drum circle might claim to. Or, to put it a simpler way:

If you think you know what the hell is going on, you’re probably full of shit.— Robert Anton Wilson

What’s more, science (those guys) is uncharacteristically quiet on the subject, because the Scientific Method can only probe the ‘objective’ reality that we all (seem to) share, but has no means or measurements which apply to the ‘subjective’ realm of qualia and experience. We can see blood activity in brain scans and we can ask for the subjective feedback of a human adult subject, but we can not make an experiment which sheds light on what it is like to see colours, think like your partner, or be Mel Gibson (luckily).

In other words, while science, maths, and language seem to point towards the common-sense, Occam’s razor conclusion that we are all sharing an objective world, we are all experiencing all of this objectivity, subjectively. We all live on the same planet, I hope, but we see it through 7 billion+ separate, subjective lens. This is the final veil that we can not peek behind. It is the inbuilt limit to the kind of understanding we would like to have of the world, because we can not find a better position to observe the back of our own heads, no matter how hard we pull on our ponytails.

We call this absolutely massive nightmare, rather cutely, The Hard Problem of Consciousness.

Understanding the depth of the riddle that consciousness poses is to understand much about the world, because it is the space in which religions, cults, spiritual mumbo-jumbo, looney ideologies, and other faith-based systems can operate. It is the blind spot of science, and the weakest link in all of our collective ideas about the world – because science is only a methodology for testing truth claims, which is what makes it so remarkably effective at dissecting, labelling and predicting the mechanistic, materialistic, and physical laws of our universe, yet why it can shed little of worth on the rather inconvenient fact that at the base of every experiment, theory and conclusion about our ‘objective’ reality, there is an inevitably subjective second layer, with simply no conceivable way to penetrate it from a place outside of ourselves.

This should be the source of our sympathy with non-harmful, faith-based beliefs: that all of the religious people born in Salt Lake City, Utah, or Belfast, Northern Ireland, or Dabbiq, Syria, are born with an infinite fucking hole in their sirloin steak heads, where Nothing and Everything seem less like the opposites they’re supposed to, but more like equal sides of the same ancient mystery. As the absurdist writer Alfred Jarry joked out loud, just before the passenger next to him suddenly decided to walk home three stops early:

God is the shortest distance between zero and infinity.

Now, I personally don’t consider myself spiritual or religious, but I’m certainly obsessed and confused on a day-to-day basis with the fact that I am a Consciousness – and I live my life, as much as I can or remember to, marvelling at and cherishing the mind-bendingly weird, wondrous and impermanent nature of this experience I call ‘me’. Indeed, ‘consciousness’ is just about the one thing – as a science-nerd and woo-woo-skeptic – I’m willing to happily apply the word ‘magic’ to. It’s magic to be conscious. There, Richard Dawkins, I’ve said it. Life is – or can be – a merry-go-round playground in fucking Narnia. We are not just alive, like grass – we are magic unicorn creatures, frolicking around in a literal Garden of Eden gravity-dent in space-time, witness to some amazing tangible dream of a reality where nothing and everything seem so suspiciously interrelated we have to invent words like GOD just to fill the gaps where no other words will go.

Woah.

“Is”, “is.” “is”—the idiocy of the word haunts me. If it were abolished, human thought might begin to make sense. I don’t know what anything “is”; I only know how it seems to me at this moment.– Robert Anton Wilson

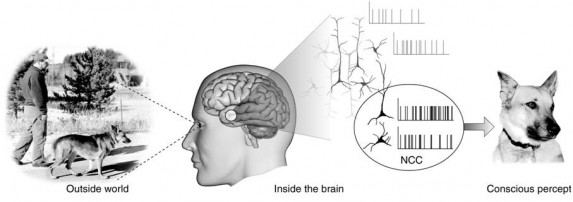

The way I like to think about consciousness is this: there is seems to be an objective world – the one we all share, and poke under microscopes – and a subjective world – the private one we tend to believe is between our ears, neck and hat. More importantly for our purposes, though, there seems to be something inbetween these two realms of thing: our selves – i.e. our thoughts, feelings, and personalities – or, in totality, our subjective perception of the objective world. It feels like we are in the middle; the overlap in a Venn diagram of reality. What we perceive, feel, think, remember, understand, believe, have faith in, even what we don’t know, is the lens through which one passes into the other; the funnel through which the universe pours into us. Here is a diagram, which contains a cheeky bit of science:

Look, in the middle… science!

And our ‘perception’ – luckily – is something that is seems to be a great deal inside our control, in the easy to comprehend ‘glass half-empty, glass half-full’ sense, (whether we have Free Will or not). This is probably the greatest blessing of the human mind: it has (or can have) power over itself. We can learn new ways to think about things; we can improve the ways we think about things; we can think better, smarter, healthier, happier, wiser, and there’s absolutely no good reason why we wouldn’t be able to. The play in the theatre might be the same, but we can watch it from a ten thousand different seats.

In other words, our experience of the universe is programmable, because – subjectively – we are all riding around in our own customisable personal universes of one. We possess then the only tool we need to hack reality, as reality appears to us. The world is a gym that our minds can get fit in. (Yuck!)

The voices in our heads can be healthy, or at least healthier, and it’s plainly obvious that some people’s minds are stuck in horrible old habitual patterns, completely unexamined, broken since childhood, badly configured to process the raw data of living, blocked off to any possibilities of self-improvement, operating instead like finely-tuned instruments that have been calibrated only to annoy themselves.

If these sorts of people could be persuaded to point their attention ‘inwards’ occasionally (yuck), they could perhaps learn to recognise this, or disassociate themselves from the automaticity of their more unhelpful thoughts, and thereby create a space for themselves to have new, different, healthier reactions. This harmless little idea was the great revolution in psychiatry that birthed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), the basic premise of which is to train practitioners to notice when a habitual thought pops up like ‘I need a drink’ or ‘I’m such a shithead,’ and then think, ‘oh, look, there’s that unhelpful thought again, right on time. Ha, silly-mind-voice that I’m not in control of.’ CBT – available on all good health services now – actually has a lot in common with mindfulness, which is probably the closest English word to the Buddhist idea of Vipassana (‘Insight’) meditation, which is probably the closest Tibetan idea to occasionally listening to the incessant jabbering going on inside your mad fucking head.

Oh, hi. At this point, having just prescribed meditation to you and everybody, I should probably confess something: I still don’t actually meditate. Sorry. However, the important thing to know here is that I used to not meditate in the same way that I used to not do homeopathy, aromatherapy, and crystal healing. Now, though, I don’t meditate in the same way that I don’t eat more vegetables, jog, or get up early, which is better.

I’m very wise.

Luckily, though, I think it’s even possible for hopeless slobs like me to steal some of the low-hanging fruits of meditation, just by understanding what it is, what’s it for, and why one might choose to do it at all. If you were at all like me, imagining meditation as little more than a relaxation technique for boring people, you might have missed roughly the whole point of it being a readily available mode of attention. You don’t have to be cross-legged, closed-eyed, humming ‘om’ in a forest, and not vaccinating your children. You are instead quite free to ‘meditate’ – i.e. notice the incessant jabbering – whilst you do all kinds of normal, unenlightened person things, like walking down the street, cooking an egg, or gawping at a smart phone as you wander into traffic.

I plan to start, the way I plan to start lots of things (please note: no guarantee I’ll start.) The method will be, I think, to start with an amount of time so low that it is impossible to fail, then adding tiny, tiny amounts of time each day, until I eventually reach a point that – without even really trying – I am no longer a hypocrite.

There is only one corner of the universe you can be certain of improving, and that’s your own self.– Aldous Huxley

If we realise that our experience of reality is all we have/are, this realisation – and more importantly, the intentional practice of noticing/utilising it – bestows us with great power over our lives. We can be responsible – to a large degree – for our own happiness, and for overcoming our own problems. Of course, some harder to mediate chemical and physical processes will always be running parallel in our hardware (endorphins, serotonin, dopamine, oxytocin, adrenaline, cortisone, etc.), but we can nevertheless do a lot for ourselves by consciously choosing to upgrade the Operating System of our ideas, thoughts and world-view with a myriad of software. Common tools for self-improvement include philosophy, drugs, meditation, therapy, nutrition, exercise, art, travel, self-help, Stoicism, cold showers, and ignoring Donald Trump until he goes away.

If our ‘happiness’ and our ‘sadness’ are taking part ‘in our heads’, if they are products of our thought processes, if they are directly interrelated with our beliefs, then it seems entirely logical and sensible to say that changing the way we perceive the world – and here comes another classic half profound/half inane soundbyte for your collection — can often be as good as changing the world.

If your brain is operating on the irrational Belief System of racism, for example, you can upgrade it, and instantly find that the same world you’ve always been in is suddenly a lot more full of friends. If your brain is operating on the irrational Belief System of unconsciously, unthinkingly plodding through life on un-choosing inertia, you can upgrade it, and instantly find that the same world you’ve always been in is suddenly a very elastic realm of near-infinite capacity for change, quite ready to accommodate and absorb any new and different life you might prefer to live in it.

You can choose not to be the victim of your own biography.

You can choose whole new characters to play in this drama.

The “rest of your life” – the only bit worth worrying about – begins, always, now.

This is the hippy dream and the New Age mantra – that the world is what we make it. Yet due to our discovery and increasing understanding of neuroplasticity (the brain’s structure is not static, but remains flexible long past childhood), and neuroscientists’ increasingly clever use of fMRI machines as a scientific tool, there’s promising evidence – although it’s early days – to support claims that healthy habits and beliefs might actually be having corresponding good physical effects on the brain itself (1 / 2 / 3). It certainly doesn’t seem naïve or controversial to believe this, or the implications of it, especially in the subjective light of inspecting our own consciousness and identifying its character as the pivot upon which our whole lives balance.

Every new fMRI machine now comes with a monk

If our thoughts and feelings have the tendency to come and go, automatically, apparently beyond our conscious control, abstractly overlaid on the cinema experience of our own personal realities, then this endless show of private words, images, emotions and concepts in our inner lives has the potential to drag us along on all kinds of bizarre and convincing agendas (ISIS), unless we’re occasionally checking up on them like a nosey parent at a locked teenager’s door. What’s more, it’s actually this unconscious mechanism of thinking–whilst–not–noticing–that–we–are–thinking that is the main barrier to ‘connecting with’ (noticing) the profound reality of the endless, flowing ‘present moment’ we find ourselves wrapped in.

It is always now. This might sound trite, but it is the truth. It’s not quite true as a matter of neurology, because our minds are built upon layers of inputs whose timing we know must be different. But it is true as a matter of conscious experience. The reality of your life is always now. And to realize this, we will see, is liberating. In fact, I think there is nothing more important to understand if you want to be happy in this world. But we spend most of our lives forgetting this truth—overlooking it, fleeing it, repudiating it. And the horror is that we succeed. We manage to avoid being happy while struggling to become happy, fulfilling one desire after the next, banishing our fears, grasping at pleasure, recoiling from pain—and thinking, interminably, about how best to keep the whole works up and running.― Sam Harris

How can we become happy – the great goal of the thinking Earthling – if we are entirely at the mercy of our thoughts and feelings, distracted at all times from perhaps the one and only great “spiritual truth” there is to be known or found in our universe: that is, the plain, old, normal, everyday, ordinary fact of finding oneself awake in a universe at all.

Well, the wiser people of our world argue mostly that we can’t. We can grasp madly at pleasure (drugs, shopping, cake), and flee madly from displeasure (feelings, exercise, death), but we cannot make progress towards any more sustainable goal, if we’re just going to be hedonistic pussies about it. If some brand of happiness, contentment or elevated self-worth is really our project in this world, and its hard to think of a better one, we cannot remain cut adrift in our lives, with our emotions dictated by the chaotic whims of a vastly unknowable exterior environment, and our thoughts frothing up from some infinite, unknowable well of internal insanity. No thanks, life.

We could instead peek into this inner realm, in which our lives are happening. We might just find the general amazingness of our lives is only lightly hidden, just past the regularly distracting normalness of them.

Further Reading:

What, you want more words? You lunatic! OK, then, but you won’t get anything done today…

The Headless Way – a website of quick, 5-second ‘experiments’ that even idiots can use to notice profound things about themselves.

Mindfulness in Plain English – a well-written, simple and refreshingly bullshit-free “how to” style book about meditation, if the idea of trying it tickles your pickle.

Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion by Sam Harris – a great book on the topic of consciousness/meditation by a neuroscientist, philosopher, and famously nonsense-phobic atheist.

I was in the pub the other day when an alien called Zinfluu came in. (That wasn’t his real name, obviously, but they have different alphabets and I don’t want to overly-complicate things too early.) He seemed a bit over-enthusiastic and jelly-like at first, but he was friendly enough, so I started telling him about Earth. Suddenly he pulled out a map of Earth, and asks me what all the lines mean. He couldn’t see them on the surface of the planet, he said, when he arrived from the actual bloody sky in his actual bloody spaceship.

“Zinfluu,” I said, “those are countries.”

“Snargle-bargle funktong,” he replied, drunk.

“Countries, idiot, countries.”

He remained confused, which was probably the language barrier and the bungling new effects of Earthbooze.

“Right, Zinfluu, it’s very, very simple. Get off my arm. People are born somewhere, and the world is divided up into chunks, and that makes them a certain kind of person, like ‘English,’ or ‘Chinese’ probably, and so they have to do and think certain things growing up because they have social contracts with these abstract entities called ‘states’ based on the genetic and geographic accidents of their births, and they get given a tax number, and some ownership documents —get off my arm— then the states pay individuals called the police to enforce rules chosen by different groups of individuals called governments, and take money from everyone inside the drawn-on borders to fund it, then pay other individuals called soldiers to protect those individuals inside the drawn-on borders from other individuals outside the drawn-on borders that pay taxes to different groups of individuals in different geographic locations. Also, each one has a song. Now get off my arm, you tourist jelly shape.”

“Funkop nog blom,” he said, and I was shocked. He was right, of course. From his smashed and objective alien viewpoint, ‘countries’ were a baffling and dangerous, incoherent and inefficient idea. More importantly, though, they just weren’t real, even though quite a lot of people seemed to be constantly pretending they were.

And if anybody knew what wasn’t real, it was Zinfluu, because he was a redundant narrative device. He touched my bum in a silly way, then disappeared.

Despite photographs from space seeming to prove that Earth has just one big, basically connected, dry, green bit, the majority of people on that one big, basically connected, dry, green bit still seem to prefer the conclusion that it is actually made up of around 200-300 entirely different and separate parts called ‘countries,’ ‘territories’ and ‘colonies,’ the number of which is decided internationally and unanimously by the last person to edit Wikipedia.

This mode of thinking — statism — if we want to slap a name sticker on its old, wrinkled face, has some immediately obvious and bizarre effects.

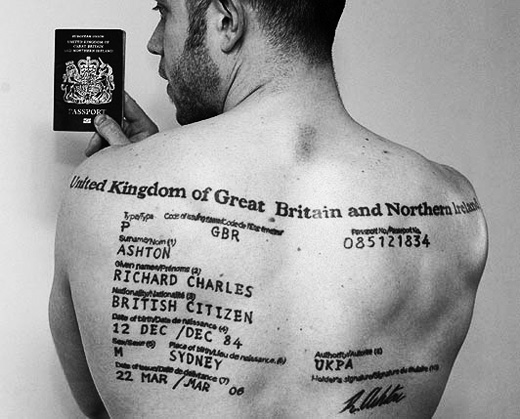

Firstly, it means that human beings have switched, only in the tiny, last percentile of their total hairless existence, from a free and nomadic species of upright monkeys that generally roamed around and put stuff from trees directly into their gobs, into a curious and unprecedented animal where almost every new member that is born is immediately, slightly owned.

Despite not choosing the longitude and latitude of our mothers at the instant we emerge from their vaginas into all this bloody nonsense, we can not leave whatever involuntary territory we land on without the sanction of the government that says it’s theirs. We can not own land or property without the sanction of a government, or trade legally without the sanction of a government, and will always have a portion of our economic value taxed by a government, and will always have to abide by rules under the threat of violence or imprisonment by a government, and might even risk being killed for resisting any such violence or imprisonment by a government. In a weird way, it often feels a bit like we are farmed and controlled for our economic productivity by an institution we do not and could not choose. When we are not economically productive, we can be given welfare, and when we are not playing by the rules, we can be imprisoned. Both options are funded by taxation, anyway, so it doesn’t much matter for the governments, which are pretty unique amongst big, worldly institutions in that they do not produce value (which even religions do by babbling about a magic cake, then passing round a sparkly hat). They can only take value, then redistribute it. This is accomplished through regrettably violence-backed taxation, the manipulation of currency, and odd ideas like deficit financing, whereby national debt is created to make potential people who aren’t even alive yet pay for stuff now. The money is borrowed by today’s politicians (or today’s people, if you’re democratically inclined), in the knowledge that it wont have to be paid back until they are well out of office, we are all out of work, and an entirely new set of humans face our tax bill.

So it is that we are still born into a kind of modern, comfortable slavery, kept in place by an increasing number of abstract restrictions, growing upwards towards the hidden guns that keep us working; only just alive and already owing money (a problem made worse if you’re born in the Christian side of the soup, and have a second, spiritual debt to a friendly hapless Jew who died way back when a road, a sewer, a workplace and a kitchen were all the same thing…)

The second problem with statism is how inconsistent it is with any rational attempt at morality. While ethical issues are of course difficult to define, what should be obvious to anyone smart enough to make a sandwich without getting trapped in the washing machine is that there are no such things as ‘good’ and ‘evil,’ and the absence of these convenient but fictional absolutes means we have to give our brains, not Father Christmas or other supernatural creatures, responsibility in figuring them out. However, consistent moral principles do not apply very easily to the world of states because there is such a noticeable moral hypocrisy at its core — in that its basic mechanisms for functioning are not unlike theft, threat, debt, and violence, which we are almost universally told are wrong when other children do them in the playground — and an inconsistent web of contradictory laws on its surface — where the exact same action can be deemed moral/legal or immoral/illegal, depending only on your geographic location, and not on its intention, justification or consequences.

Our ethical priorities might always be warped when we trust the paradox that a murderer is always bad, but a soldier is always good, despite the difference only sometimes being a uniform and a paycheck; or that theft is bad, but when you call it taxation, it switches suddenly to only goodness, as if stealing stuff is not actually the problem, just as long as you share it afterwards with your favourite friends. Similarly absurd nonsense will also exist as long as different states continue to enforce ‘morality’ on their citizens, and national boundaries mean you can do incredibly silly things like start a bottle of wine as a law-abiding citizen, then walk across an imaginary line and finish it as a merry criminal, or have consensual homosexual sex too near the wrong border, and be one small act of bum fun clumsiness away from an illegal orgasm being the last one of your little gay life.

While you might argue that states, in general, exist exactly to protect you from such nastiness, it is important to remember that ‘your state’ fully controls the police, the military, the law, and the legal system, has exactly the bottomless funding that you don’t, and naturally (like any organism or organisation) wants to protect, sustain and advance itself, so will always – at a push – use those resources in whatever way it deems necessary and essential for its own survival. It wont vote for its own non-existence, even if 51% of its citizens demanded it. This is, of course, regardless of what is in your interests, or anyone else’s interests, or ‘the Planet’s’ pesky interests, and regardless of what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong.’ The late comedian George Carlin said it best: “Your ‘rights’ aren’t rights if someone can take ’em away. They’re privileges.”

Still, I guess all that is irrelevant when you live in a good country.

Now I know I’m waffling on about the subject of taxes a lot, and that’s about as sexy as eating pickles from your hand on a speed-date, but it is basically one of the most important riddles to unwind if you want to penetrate why this world isn’t as nice as the one John Lennon tried to achieve by heroically spending a whole day in bed with Yoko Ono.

Because when we talk about what a ‘country’ actually is, we are not talking about a group of people (a culture) or an area of land (a region), we are talking actually about the limits to which one institution can tax a group of people in an area of land before before another one takes over. Apart from making patriotism seem a less glamorous thing to celebrate (“We were born in a place where we are taxed by the same organisation! Amazing! God save the Queen!“), it also exposes a core goal that countries might just share with businesses, advertisers, cults, and the ‘business’ religions: to get your money, and keep your loyalty, by convincing you of their own virtue, particularly compared to the virtue of their competitors.

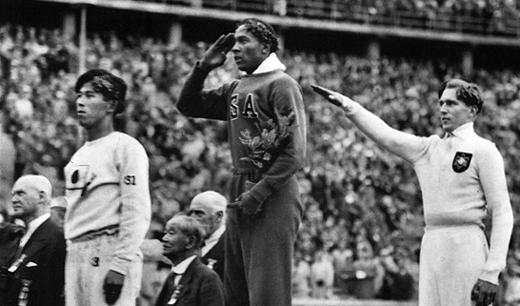

“NAZI WANT TOUCH CHOCOLATE MAN”

The difference between businesses, advertisers and (to a lesser extent) religions, however, is that they do in some way have to earn our money – to tickle it out of us – by providing something of value (religions sell us ‘salvation,’ the alleviation of guilt, etc.), whereas our governments inherently do not — they can just poke us with a gun for our money, and not let us poke back — and that is why they can afford the luxury of getting their greasy sausage-fingers all over welfare programs like public education. Then, time and time again, what ‘we’ learn in state-funded schools gravitates towards a narrative that firstly defines ‘us’ as a group with shared values and heritage (which muddies our idea of what a country really is), and then secondly, writes that fictional group’s role into a fairytale remix of history as the good guys, even if that version of real events is so untrue it could somehow ruin a horse up a tree from a mile away.

Thus in England, they train lots of new English people, and in France they train lots of new French people; they all get taller, hairier and more boring at roughly the same speed either side of a bit of water they could swim across, and suddenly find themselves adults who magically believe they’re different, and are proud of that difference.

Ignoring the obvious Darwinian spanner that all of them are some level of immigrant anyway — because humans don’t come from magic forest space eggs, silly — their patriotism represents nothing but an unearned smugness in the recent achievements of other dead souls who were born on the same lump of taxed land as they were; and worse, a silly celebration of the skewed historical baggage of ‘their people,’ which isn’t really the history of ‘their people’ at all, but the history of the rulers of ‘their people.’ Peasants never huddled around either side of the sea experimenting with elastic so they could fling themselves at each other for a nice war. No, they had to be rounded up, convinced, paid and ordered to fight by someone with a more impressive hat. That’s why patriotism is always valuable to the owners.

Before you know it, you could be this thumb with ears

I was born British, it seems, because the little book I need to leave my drunk, wet island says so, and I remember learning in school how ‘we’ beat evil, imperialist Nazi Germany in World War: Part II, but not how the same unpleasant, imperialist ‘we’ brutally occupied Ireland or India, or, well, The World before that. I only remember learning Winston Churchill’s ‘heroic’ role in defeating the axis powers on the battlefields of Europe, but not about his queasier role in the simultaneous starving of millions of people in India (“I hate [them]. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion.”) I remember learning how ‘democracy’ was supposedly wrestled in this country from the aristocracy and landed elite, but not about the bloody and brutal origins of its entirely unelected monarchy.

‘God Save the Queen’? Umm… why, exactly?

Like most children, I was only given half of the story of ‘my country,’ and, rather conveniently you might say, the half I was missing was the half I needed to evaluate it even-mindedly. Of course, you could fart yourself into the sky, and enjoy the same rose-tinted shit any where you land. In the most American parts of America, for example, their patriots trumpet democracy, liberty, freedom, The Constitution, the Founding Fathers, defeating fascism, and that American Dreamy Thing, with considerably less painted belly-wobbling over the inconvenience of native Americans existing, the wealth built upon slavery, McCarthyism, the internment of Japanese-Americans during and after the War, its napalm, its nukes, Guantanamo Bay, or just about anything the bloated bully caricature of a country does across the world now with its corporate and military might, too often in direct and almost hilarious hypocrisy with its stated ‘ideals.’

The problem is if we are teaching children stuff that’s wrong, and indeed that seems to be one of humanity’s specialist subjects, then schooling is more like a conveyor belt system for patriot-rearing than genuine, agenda-less education. We all laugh and scorn when we see the heavily indoctrinated children of fanatical groups like the Westboro Baptist Church (the ‘God Hates Fags’ lot), yet we only mock them because the things they are rigidly taught as children are so different to the things that we are rigidly taught as children. Swap the cosmic accidents of our births, and, without independent thinking, we would be on the pavement telling God who He doesn’t like, and they would be us, reading this blog, perhaps, and feeling slightly annoyed at the comparison to such dappy sign-crayoning twonks. (And if you are reading this, Jael Phelps, you’re probably the hottest girl who has ever despised everything I stand for.)

If you want to understand why there’s so much conflict between the slightly varied shades and shapes of humanity, it’s because American children learn how ‘they’ defeated the British, British children learn how ‘they’ defeated the Germans, German children learn ‘they’ defeated the French, and the French children presumably have an extra hour of maths or cigarettes.

The teams are invented; the histories are faked; the virtuous feel-all-nice feeling is fabricated.

After that, there is also Nationalism, which you can grow by locking Patriotism in the basement for a year, feeding it a diet of sugar and batteries, and repeatedly kicking it in the head with a flag-painted sex toy glued to a shoe. Nationalists, like the dildo-battered, cross-eyed dungeon gimps they are, not only insist on the virtues of their country, but also tend to believe that their country is better than all others.

George Orwell, who is generally more right about most things than most people, called Nationalism, “the worst enemy of Peace.”

As we probably didn’t learn earlier from Long Rant Part I, it is important to (try to) apply logic to have consistent moral beliefs. For example, if we believe that soldiers are good and brave and sexy because they ‘fight for their country,’ then logically we must extend that viewpoint to all soldiers from all countries, as all soldiers must believe the same. Yet then, something funny happens. Suddenly, war stops being the simple Mel Gibson-friendly good versus evil story of history.