Life: the ultimate near-death experience

According to numbers and science and stuff, 100% of us are going to die. That’s a lot.

Yet despite this important, common event being one that we will all share regardless of race, sex and bank balance, the fact of our mortality is the one that we collectively seem the most poorly adjusted to. It’s the topic that we try to think and talk about the least to avoid unpleasantness, and yet the one that has caused the most problems for our species since we became the only animals clever and arrogant and silly enough to start worrying about it. Indeed, Professor Numbers from the University of Guessing says that 90% of the people on the planet are still so afraid of dying that they spend their entire lives pretending that they won’t, and choose instead to believe that they’re going to come back immediately as a butterfly or live forever in a big cake in the sky.

The reason that these childish fantasies have persisted through thousands of years of science, philosophy and logic, is, of course, that we still don’t know what happens when we die. More specifically – because we do know what happens when other people die (they become suddenly, infinitely boring, then later smell funny and melt) – we do not know how to reconcile our weird, subjective experience of reality (our consciousness, or ‘soul’ if you want) with the idea of an objective universe without us in it to experience it. Sentences like that aside, we literally can’t imagine not existing. We’re very used to it, and we’ve never experienced the opposite. It’s impossible for us to think about what it’s like to not think.

Yet we know that one day we are going to die, we know that every living second brings it closer, and we know there is absolutely no conceivable way to cheat it.

It is no wonder, then, that the lack of any right answer to a question that fully changes everything terrifies us more than the thought of being locked in a room with Mel Gibson and some gin. And it is no further wonder that the impossibility of disproving any claim about death is what protects religions’ attempts to have a cheeky guess, and why so many people so desperately want to believe those guesses, regardless of how little they seem to map coherently onto reality or explain anything satisfactorily.

However, just because we cannot be Right does not mean that we cannot be Less Wrong, and luckily we don’t even have to die to realise that some of humanity’s biggest, or at least latest, theories aren’t entirely convincing. Take the Judeo-Christian idea of Heaven, for example, which looks absolutely lovely in the brochures, but makes about as much rational sense in the real world as trying to give a surprise reflexology massage to a sleeping alligator.

Indeed, we can forget entirely that Hell sounds exactly like the kind of place humans would invent to scare their kids into eating their peas. Or that separating people in to ‘good’ and ‘bad’ is a moral system about as complex as Kanye West’s level of self-awareness. Or that concepts like pleasure are entirely impossible without equal and opposite kicks-in-the-balls to compare them to. Finally, we can notice that the whole idea on offer to us – when dissected – is a bizarre tangle of contradictions, impossibilities and paradoxes.

The idea of the Christian afterlife (and no other major religion is much different) is that a Being who exists separate to everything in our universe in an unknowable dimension outside of space and time, who has existed forever, don’t ask, apparently not evolving, created you, specifically, and your appendix, in a different dimension inside of space and time that he controls, with a master plan, and free will to choose for yourself, obviously, don’t ask, because he loves you, ignore those fossils, but judges you, because he knows everything, Jesus, and can change everything, praying, then judges the sum worth of your obedience, forgiving you, sort of, on a simplistic binary scale of human behaviour from the separate and unknowable dimension, angels, to choose whether you should once again rejoin, somehow, that separate dimension outside of space and time, without sin, to exist as yourself, again, but forever, not evolving, don’t ask, or go to a third dimension, separate to all other dimensions outside of space and time, but hotter, which is for naughty children and quite often gays.

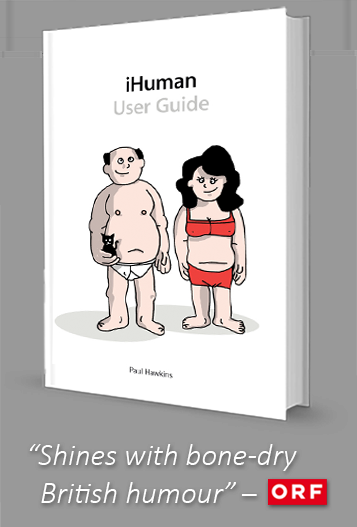

White, handsome Jesus explains his appendix to some tramps

It’s all about as lovely-sounding and unlikely as the sky raining books on an open-air Justin Beiber concert. Still, I hear you ask, why would you want to strip this comforting illusion from someone, you smug, awful swine?

There is a common opinion, I think, that because atheism or science or mushrooms or yoga do not provide any consoling alternatives to the Afterlife that this freedom-from-facts is supposed to make good and rational people tolerate religious beliefs, no matter how bonkers they seem when you bullet-point them on a badger, as long as they do something, anything, to help people cope with the potentially agonising dilemma of impending Death. And it’s very hard to argue against the idea of giving a little comfort to someone who is frightened or grieving without looking like the kind of prick who would kick down a sandcastle, for almost the exact same reasons that it is easier to continue certain other simple lies rather than confront a difficult truth. But there is, I think, an extremely urgent, important and humane reason to challenge these beliefs.

Children believe in Santa Claus because a lot of us adults tell them that he is real. In one way, it’s an abuse of our supposed moral and intellectual authority. Children ask us questions about how the world works because they’re truth-seeking, pooey little curiosity-machines, and then we tell them about flying, bullied reindeer, magic slave elves who prefer rich kids, and obese jolly men who disobey property rights and work for Coca-Cola. Of course, this is generally regarded as an OK lie to tell, because it’s a pretty weak tangle of fibs that falls apart on the first tug of the tinsel. Children should work it out fairly young as long as you don’t drop them too much, and adults should admit to their collective deceit quickly unless they want to seem daft and confusing to a nine year old.

The child cries for an afternoon, Mum apologises through the door, Dad has a brandy, Granddad falls down a manhole, and everyone carries on as normal with just some minor trust issues that therapy can always iron out later.

However, imagine for one christmassy minute that a child starts to wonder if Santa Claus is real, and asks their parents, who insist that he is real, but who eventually get angry, upset, or end the conversation if it persists. Imagine if the same child kept asking other figures of moral authority – teachers, priests, politicians – and they all maintained that Santa Claus is real, got upset or angry or offended when the child kept asking, then also refused to continue talking about it. The two options for the child are obvious; he would either continue to believe in Santa Claus because it is too weird and painful to imagine that all of the sources of moral authority in his life would repeatedly lie to his face about their lack of knowledge, or he would be ostracised from the collective fiction by the Truth’s inevitable ability to expose liars, frauds, dicks, and sneaky, pretend present-givers.

This is, of course, atheism’s relationship with religion in far too much of the world.

Some people find it extremely difficult to hear because religious beliefs are almost universally protected, pandered to and pussy-footed around, but there is a reason that we’re afraid of death, and afraid to talk about it.

It is because religion cannot prevent our fear of death; it can only create, prolong and protect it.

Pope throws ‘Dove of Peace’ from window. ‘Dove of Peace’ ignored by Crow of Nature

It gives us the flimsy promise of an afterlife in exchange for our blind, unquestioning trust. It dangles the incentive of eternity in front of us, a reward for our earthly loyalty, and then tells us to close our eyes and wait for it. It performs a crafty but unconvincing magic trick, on children mostly, that simply defines mortality out of existence. Disregarding how much people really trust their faith, and I suspect the truth of that is masked often by the real, psychological harm inflicted on young minds by lying and emotional blackmail, religious beliefs are so profoundly damaging because they arrogantly divert us from perhaps the most important question of all:

What if we’re temporary?

There is absolutely no reason to believe there is an afterlife, at all, and the people most likely to find that hard, sad or scary are the people who have always had their fingers in their ears, deluded themselves into passivity, and naively extended their existential expectations to the borders of infinite.

These people aren’t stupid. They’re not fools. Their irrational beliefs aren’t the product of an intellectual shortcoming of any kind. The reality is far sadder. They are the victims of a subtle but lasting dogma. They were told what to think by all those who claimed to care most about them in the world, people whose good intentions were only perhaps matched by their inadvertently disastrous results. To question certain beliefs, unfortunately, is to question the authority and moral good of the people who believe them, and there are strong emotional and social stigmas in place that make that difficult. Religious people are often the first to ‘take offence’ if someone asks them why they believe a ghost talks to them or how fish can become wine or whatever, and this is normally because its embarrassing to hold beliefs that can’t be explained beyond the word ‘faith’. By telling you that you can’t talk about an idea without a person being simultaneously insulted, they’re saying that you are choosing to break the social contract of basic politeness by bringing it up at all. This makes you the dick (even if you’re doing something not dick-ish, like defending gay marriage or women’s rights). It’s all very clever.

You can see the dogma in action, I think, in the way some people live their lives – especially when it looks like they’re not living them at all, but just trying to get through them as quickly as possible and without dropping too many jars in the supermarket. The worst offenders follow The Rules, whatever they’re told they are by anyone with a haircut, place their happiness inexplicably in collecting things, carbon-copy the lives of their parents, look increasingly like someone with a bag of charity shop clothes and a cruel sense of humour has mismanaged a walrus, and grow old and fat and slow in a house never more than 80 footsteps in any direction from the bit of land some vagina or other plonked them on to.

Death is a really important thing to adjust to, and not to hide from as we are so actively encouraged, because it should be the biggest driving factor of how we choose to live our lives, decide what we want, and manage our health and happiness. You are going to die, so is everyone you know, that inevitably is governed by no rules or regulations about how, why, where or when, and as you get older with those around you, it will become an increasingly regular part of your life, and, as looming, indifferent and ever-nearer a certainty as the next Fifty Shades of Twilight mass-paper-tragedy.

Think about how quickly it felt that you got to where you are now, and then imagine, if you can, how quickly the second chunk ahead of you will go. There is no time to waste, really, and you will never be younger than you are now. There is no afterlife for you in any form that is like you are now — this is it, right here, right now, and it shouldn’t take the clichéd near-death experience to trigger some productive, excited urgency deep in your bones. Life is the near-death experience.

If the thought of death still scares you, part of the problem might be that a society in the grasp of collective fictions and cultural narratives has failed to adequately carve out the space for you to adjust to it healthily. If it feels like a kick in the head now, at least you know it’s a kick in the head when you’re napping on the train track. It might be painful, but it’s the radiotherapy that will cure the cancers of fear and doubt.

We should think about death, a lot maybe, and we should talk about it, and we should carry it’s presence around as a proud and constant millstone on our necks – not because it is depressing or frightening, but because it is what reminds us that we are alive now, and that we won’t be for long, or forever. It should inspire us, motivate us, help us forgive, forget, and remind us not to worry about what we can’t change, or scream at us to repair our priorities from the bizarre and crazed arrangement that society now encourages.

Have a bit more fun, basically

And once you’ve killed the delusions of religion and refused the corrupt pledges of an afterlife, there are a lot less reasons to be afraid of death. Maybe even none. There will be no final judgement on your character, no hierarchy in which you will be assigned a place forever, no eternity to anguish over your mortal mistakes, and, healthiest of all, no lasting reasons to despair over the deaths of others.

Amy Winehouse, as we all found out by text message, recently and accidentally boozed herself dead, with the final coroner’s report concluding that she died of ‘misadventure,’ arguably the most fun-sounding of all the possible causes. The whole episode was pasted in the news as a tragedy, and it was of course, but for us, I think, not her. She was watching telly and listening to music, steadily glugging her way through several bottles of vodka, slipping numbly and unknowingly into her Last Sleep – and, perhaps for someone who seemed to fit so uneasily in this world, release. She started with nothing and ended with nothing. It is us who suffer, grieve, weep and wonder in her wake, or wait for a sombre, slapped-together collection of B-sides at Christmas, while she, simply, does not exist any more. Her deathday was shared by hundreds of thousands of others on our planet, as ours will be, yet the fact that we cry most for those we know best should be the biggest clue to the personal fear at the heart of our grieving.

We have lost something, the Dead have not. Funerals are not for them.

Because when we die, we are not there.

When your time comes, it is not you who will die — it is the universe that will end. Your lens upon the universe will close, and it won’t be there any more.

There is nothing to be frightened of, because you wont be there to be frightened of it.

That’s beautiful.

Death is not a call to Futility and Depression. It can be nothing, I’m sure, but one loud and desperate, pleading Call to Arms. To adventure, experiment and investigate, to dare and dance and drink, to race and run and fight and fall over, and get back up, crash around, and do it all again every day your body lets you; to trade pleasure with pain however you can, and to grow and change and fix yourself; to laugh at Fear and Doubt when they whisper their more pathetic noises in your ear, to cram as much love and laughter in to your life, and as many good others as you can find, as you can, while you can — to live as one big shiny, screaming Fuck You to whatever indifferent forces dropped us here without a map or purpose, and an even bigger one to whatever now keeps us from living how we want.

Death shouldn’t be the handbrake that leaves us rusting in some garage of our own invention, but a red and seductive pedal clamped to the end of our legs, that wont release us until the cliff edge is behind us, the canyon’s fall in front, and all we can think as that Last Wind rushes through our hair is what a great, mad ride it was when we really, really wanted it to be.