Aliens: I’m so sorry, Brian Cox

The gigantic smiling head that orbits our planet belongs to a man called Brian Cox. He’s a particle physicist, university professor, mother arousal specialist, and television presenter who makes decent science programs about space for the BBC.

He seems like a nice, cheerful sort of a chap — certainly the kind of person that you would rather hire a boat with for an hour than purposefully misdirect towards a sniper battle in a landfill.

So, in a pub last week, if I had been the Supreme Leader of Planet Earth instead of just mildly alcohol poisoned, he was the person I would have chosen as my ideal ambassador for humanity in the eventuality of aliens ever landing here.

I think I owe Brian Cox an apology.

One in a sillion bananillion gorillian

‘Aliens’ almost certainly exist. If you don’t think they do, it might be that you have just momentarily forgotten how big the Universe really is. Have a little click around this for a cheeky refresher – and remember that this is just the tiny, tiny bit of our galaxy that we can see and take photos of – or just look at this 75mb gif I’ve made your computer download…

Space is a silly, silly place.

Each one of those dots is a star like ours, and a source of energy to the planets caught in its gravity, just like ours. Each is a hub in space for all of the same elements we’re made of, and each is governed by the same physical laws that arranged those elements into something like us.

There is estimated to be between 200 and 400 billion stars in the Milky Way, our galaxy, and at least hundreds of billions of galaxies in just our bit of the Universe. Not that these numbers mean anything beyond stonkingly flipping massive by this point, especially considering that this pesky Universe of ours hasn’t proved itself to be anything but infinite just yet. Basically, we might as well say there is a sillion bananillion gorillion stars and planets for the amount it helps our tiny monkey minds to comprehend the situation.

The point is: it’s incredibly improbable that we are special.

Space

However, the reasons that aliens almost certainly exist are also the exact same reasons why we will probably never meet them.

Furthermore, they are also the exact same reasons why we never want to.

Our nearest star, Proxima Centauri, is about 4 light-years away, or 24,000,000,000,000 miles from us. To barely put that in some form of perspective, the interstellar probe Voyager was launched 33 years ago, and has only just begun to breach the edge of our solar system 10 billion miles away. It will be another forty-thousand years before it reaches even the very nearest planetary system to us.

Me, you, Earth, the solar system, and even Brian Cox’s massive floating head are all effectively lost in this cosmic quarantine. Considering that our Milky galaxy alone is 100,000 light-years from end to end, even the 100 light-years that our radio broadcasts have travelled so far seems as about as significant as a widowed ant’s anniversary plans.

Huge Cox

The space that we’re hiding in is just so empty and massive that the statistical improbability of advanced alien civilisations finding us is so great that you could assume the word astronomical was invented for occasions just like this sentence.

Astronomically Unlikely

Of course, this is all based on the slightly smug assumption they would want to find us at all.

There are more stars just like ours than there are grains of sand in all of the deserts in the world. So, if life exists here and in at least one other place (where the aliens come from), then it’s logical to assume it exists everywhere.

Unhelpful amounts of galaxies

Suddenly, we’re not the special, magical wonderstuff that invented trousers and bread; we are insignificant, common, generic.

Like every commodity in existence, life is worth less when it is in abundance. We treat pandas kindly because they are rare, but we’ll happily plough a minivan through a parade if we think there’s the slightest chance we might kill an extra wasp. Aliens, if they do somehow find us — and that’s generally the kind of thing they like to do — would probably have found so many other planets and life-forms that they would regard us with roughly the same level of enthusiasm we’d devote to Paris Hilton’s opinions on anything more complicated than a sausage.

The chances are that they won’t fawn over how impressive we are, or invite us to join some intergalactic ride-sharing space union, or begin imparting their advanced scientific knowledge to us.

No, they’ll probably stop for a photo, giggle at an aeroplane, and move on.

Like us?

The other common thread running through many science fiction stories and UFO conspiracies is that we, humanity, want to meet aliens because they’ll probably be somehow like us, humanity.

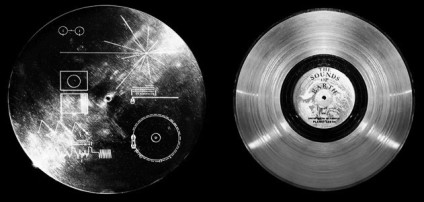

Even NASA, which you’d assume must contain at least a few people you could trust to hold a hot coffee without dipping their ears in it, seems to subscribe to this idea. When they launched Voyager, they placed on-board an especially commissioned golden long-play record complete with a map of our solar system and an audio track of uncharacteristically peaceful messages from our planet — a planet, I remind you, that has been at war almost non-stop since it was clever enough to invent nations, gods, sharp stuff and things that go bang.

(Although we’re also pretty cute sometimes…)

And right there could be our problem.

It’s exactly because they might be like us that we don’t want to meet them. To reach Earth, extraterrestrial life would need technology whereby they could travel trillions of miles in their life-spans. The human race, meanwhile, are still executing each other with lumps of metal to get the best price on a finite, black liquid we have to burn to get to the shops.

I mean, seriously, have you met us?

Think about how well humans historically have treated life-forms they see as inferior to themselves.

Ask the Native Americans how being friendly to visitors turned out for them.

Ask an African a few centuries ago how excited he was to see a boat.

Ask the dolphins and penguins in the zoo how they came to the peculiar decision to move to a fish-tank in North London.

Humans don’t discover anything and think ‘oh, look at this thing doing absolutely fine without us.’

No, we bomb it, dig it, skin it, mine it, catch it, poke it, spill it, lose it, break it, burn it, and sell it. We plant a flag for the press conference, move in the bulldozers, and then set up a gift shop selling postcards of what it used to look like.

So while “Hello. Let there be peace everywhere,” might sound like a confident message to sling deep into the cosmic dark with a trail of breadcrumbs home, perhaps we’re more like the lamb that’s rolled itself in buttered herbs and is lolloping happily towards a man holding a pita bread, a shotgun and a barbeque.

We even put a galactic map on it

These bloody aliens apparently possess wizardry that allows them to bound across time and space just for a laugh, and I was going to send Brian Cox to go and shake their hands/claws/tentacles like we’re equals? No, no, no, I’ve changed my mind. I’m so sorry, Brian.

At the very first sign of a spaceship landing, please take my lovely, smiley Brian Cox, put him in a helicopter with a pencil, and get him up a mountain somewhere to think up new ideas for super guns.

If I could choose again, I would vote for someone with at least one finger up their nose, a face that could divert traffic, and a name like Wally Fumblebricks.

Better still, send a pig in a cardigan and hope they don’t figure out we’ve got 20,000 nukes.

Image sources: [Cox] [Bigger Cox] [Believe] [Cute]