Consciousness: Your Personal Customisable Universe of One

Here are some words which have caused us an unending amount of trouble since we got cocky enough as an upright animal to try and add our cute little human meaning-labels to them:

Consciousness Existence God

Nothing The Big Bang Infinity

Subjectivity Objectivity Reality

To try and explain any of them seriously or coherently is to risk sounding like a maniac, especially in scientific terms, and even the most intense theological or philosophical writings about these clumsy words often straddle a fine line between things that sound true to things that sound so vague as to be almost meaningless. To one person, three words like “God is Everything” sound like the spiritual key to the cosmos. To another person, perhaps sitting too close to the first person on a night-bus, “God is Everything” is the kind of simple gibberish that inspires an urgent change of seats, just in case it’s followed by a touchy-feely invitation to “the magic love forest of Gaia” or an ominous-sounding shed.

For the best/worst example, look no further than Martin Heidegger, the man who one day decided to uproot 2,000 years of philosophy by noting that all of it, every single word of it since Plato, “has attended to all the beings that can be found in the world (including the world itself), but has forgotten to ask what Being itself is” (1). This pain-in-the-arse idea he called Dasein (‘There-Being’.) Here is a dense and boring quote from a summary of the 20th Century philosopher for a lovely example of how trying to say ‘true things’ about ‘profound things’ quickly produces sentences that could just as easily appear upside-down on the walls of an insane asylum in crayon:

Heidegger turns our focus away from the philosopher’s fixation on the thinking ego, towards the consciousness of Being. His attention is on what is not thought, on what is forgotten by Dasein in its thereness as a human entity. He wishes us to resight ourselves on the situation itself of being-there, as we are, at a loss in the obliviousness of everyday life. Only then can we recognise our deep fall into the inauthenticity of one-sided technological development. The risk of falling into inauthenticity occurs when the particular Dasein, which is the public ‘they’, or as Heidegger puts it, to the everyday self of Dasein, which is the public they-self.– Richard Appignanesi, ‘What Do Existentialists Believe?’

Ahem. OK. Taxi!

Remember, too, that that is from a summary of Heidegger. Dealing with the actual 438-page work Sein und Zeit (‘Being and Time’) is like trying to swim through a soup made of wood with your eyes. Delve into it if you don’t mind gambling with your sanity, and see for yourself whether you can differentiate between sentences of profound, ultimate truth, and sentences that you might otherwise expect to hear from a bearded, mad-eyed man emerging from a bin.

Well, what people like Heidegger – and every other relevant philosopher, theologian, guru, priest, spiritualist, and 4am drug-addled loony in a drum circle – are essentially going to such great, murky depths to interrogate is this: there’s an uncanny thing to notice about your/our situation in the world, that is so incredibly, incredibly, incredibly, incredibly, incredibly, incredibly weird, that perhaps the only bigger miracle than it is how you (and I and everyone) get anything done in its presence:

It’s that you/we are conscious.

If you thought ‘duh, of course I am, God did it, so what, shut up’, then there’s a good chance this article is not going to be for you. That’s ok, and I hope you have a lovely time wherever you end up next (I suggest here.) If you thought, however, something more like ‘I know, man! It’s soooo trippy! What the fuck is going on?!!?!?’, I like you. You stick with me for the next lump of your confused, enthusiastic little life, and we’ll go on a little journey into the deep heart of nothing and everything. Strap in.

I. CONSCIOUSNESS

So. Everything you hear and see and think and feel and recognise and remember occurs in the non-spatial, non-material, boundary-less theatre of your consciousness. Obviously. It is the base ‘fact’ at the root of your experience of everything; the canvas upon which your world, the world around you, is painted. Everything ‘out there’ exists – it seems – on the precondition of your being conscious to experience it. When you are not conscious – in the year 1416, for example, or when you are taking a nap/deceased – you have literally nothing to report back about reality. There is not even a reporter that could be doing the reporting.

You exist now, and, unlike basically everything else that exists, you are also aware of this existence. In a universe of atoms and quarks and photons and rock and gas and dust and brains and potatoes – ‘you’ – whatever that is – are a subjective experiencer of apparently physical, apparently material phenomena; weirdly, obviously, made up of all the same stuff that a universe might contain, yet able to ask that universe what a universe is.

You do all this in the inner abstract world you know yourself to have, the one that is currently being fed by the inputs of your bodily senses. It’s a kind of formless ‘awareness,’ locked on to a heavy reality trip, yet simultaneously capable of the limitless abstractions of thoughts, ideas, and conceptualising as yet ‘non-existent’ things, like sophisticated new jokes about your colour-blind friends.

You are always experiencing everything in this entirely private realm of your own consciousness; incommunicable and totally unprovable to any one else, just as theirs are to you. Furthermore, this consciousness generates your feeling that you are a self – whatever that is – an outwards-facing, identity-shaped lens upon the universe, staring out at it, and/or sucking it back into the space behind your eyes, where you – whatever that is – er, is.

This is all weird.

However, upon further inspection, it even seems a bit controversial to say that you HAVE a consciousness – the way you might have knees, a spatula, or an expensive coastal property you’ve hornswoggled from a dementia-ridden spinster – you, instead, kind of, ARE a consciousness. Point at your face. What are you pointing at? There’s no-thing there, where ‘you’ are supposed to be. Try it. Please. Now.

The no-thing

The philosopher D. E. Harding gave a nice, funny instruction to noticing this predominant feature of consciousness in his book, On Not Having a Head:

The best day of my life – my rebirthday, so to speak – was when I found I had no head. This is not a literary gambit, a witticism designed to arouse interest at any cost. I mean it in all seriousness: I have no head. It was about eighteen years ago, when I was thirty-three, that I made the discovery … To look was enough. And what I found was khaki trouser legs terminating downwards in a pair of brown shoes, khaki sleeves terminating sideways in a pair of pink hands, and a khaki shirtfront terminating upwards in – absolutely nothing whatever! Certainly not in a head … It took me no time at all to notice this nothing, this hole where a head should have been, was no ordinary vacancy, no mere nothing. On the contrary, it was a nothing that found room for everything—room for grass, trees, shadowy distant hills, and far beyond them snow-peaks like a row of angular clouds riding the blue sky. I had lost a head and gained a world … Somehow or other I had vaguely thought of myself as inhabiting this house which is my body, and looking out through its two round windows at the world. Now I find it isn’t really like that at all. As I gaze into the distance, what is there at this moment to tell me how many eyes I have here – two, or three, or hundreds, or none? In fact, only one window appears on this side of my façade, and that is wide open and frameless, with nobody looking out of it. It is always the other fellow who has eyes and a face to frame them; never this one.

It’s a profound thing to notice, yet it is ever there to notice.

To be something; and to know it; and to experience things as an open lens upon existence – is freaky beyond mere words. Indeed, in the 1989 Macmillan Dictionary of Psychology, a book which sounds like not the absolute worst place to go to if you wanted to understand a word relating to the mind, Stuart Sutherland said this of ‘consciousness’:

The term is impossible to define except in terms that are unintelligible without a grasp of what consciousness means […] It is impossible to specify what it is, what it does, or why it has evolved. Nothing worth reading has been written on it.

Oh, ok.

Essentially, according to Mr Sutherland, we should all be wide-eyed, gob-smacked, flabbergasted, freaked-out, awe-struck, dumb-founded, stupefied, spell-bound, and unendingly astonished in a perpetual hypnotic tsunami of speechless wonder at this thing; this experience; this verb that we are called being… except then we probably wouldn’t get anything done. And things need to get done, otherwise we wouldn’t have any cheese.

So, what do we do instead, when faced with the infinite, unparalleled mindfuck of our situation?

II. THINKING

Well, we think.

We think, it turns out, quite a lot. We’re chatting, joking, busy, lost in thought, learning something, absorbed in a book, a movie, The News, an activity, a game, work, we’re remembering, misremembering, reliving past arguments, rehearsing future ones, fantasising, fictionalising, talking to ourselves, others, pets, postmen, thinking about ageing, memories, goals, grocery lists, evening plans, about our mistakes, about dinner, about ISIS. We mostly – and seemingly automatically – let our consciousness wander throughout the day in all kinds of weird and wonderful directions, everywhere and anywhere, it seems, except inwards, at itself.

This, it turns out, is not ideal. Yet it is simultaneously not that easy to stop.

Now, I used to be very suspicious of the word ‘meditation,’ because it sounded an awful lot to my dumb, young ears like sitting alone and being quiet, two proposed experiences that a lifetime of running around yapping made me distrust immensely. The word ‘meditation,’ in my stupid-head-dictionary, conjured up thoughts far, far away from ‘normal, ordinary people like me,’ yet much closer to ‘new age nonsense hippy-dippy beard homoeopath guru weird bald monk burn-themselves people over there.’ To me, it’s four innocent syllables swam in a prejudice soup of unscientific, religious, “spiritual,” and, most importantly, boring-sounding ideas, that had no sort of relevance to a modern man of beer and science like myself.

“‘Meditation,’ you say? Hm. I’ll pass, thanks.”

Then I read some stuff about it, and, to my surprise, it turns out that ‘meditation’ is basically a synonym for ‘occasionally listening to the mental, incessant jabbering going on inside your mad fucking head.’

Which is fine, isn’t it?

So, cross your legs, get comfortable, close your eyes, whisper loving thoughts to the crystals on your Shamanic dream-catcher, and listen, just for a minute, to the mental, incessant jabbering going on inside your mad fucking head. Try first, for even ten seconds, not to think, and pay close attention to what happens. Here’s a space to help:

Did you do it? Of course not. Well, if you had, what you would have instantly noticed is that the circus is permanently in town, they’ve raided the liquor cabinet, and are now holding your mind-voice hostage. In other words, ‘not thinking’ is freakishly, frighteningly not possible. You can’t turn the damned internal voice off, so intent is it on it’s own selfish agenda of non-stop nonsense. Blah blah blah, it goes, all day long, like the Kanye West of your own head.

Meditation, at its humblest, is simply a way to notice, however temporarily, that there is a weird, distracting, and hypnotic automaticity to the thoughts overlaid on our conscious experience of the world. Here’s another space, for you to notice the next word which pops into your head. It can be anything. OK, any word, go!

What did you think of? I bet it was weird, you freak. Could you possibly explain why it was that word – not any other possible word – that came up? Did it, in fact, feel more like you were the receiver of that word; the satellite dish that caught its signal, rather than the workshop in which some rational actor inside you carved it? Presumably it somehow bubbled up from the froffing, formless, infinitely unknowable, inaccessible, neuro-chemical purgatory of your subconscious, yet we might as well say it was beamed in by space fairies, downloaded from the god-mind, remembered through a past life echo, or telepathically inserted by the Flying Spaghetti Monster on the other side of Saturn, for all the evidence that your conscious mind can muster that your subconscious is a thing that exists. Its harder still to pinpoint how you chose it. Whatever the answer, it’s useful to notice this spooky lack of authorship we seem to have over the content bumbling, staggering and meandering through the most personal and private realm of our minds.

“I’ll think of something.”

On top of that, there are our feelings – those wordless thoughts that we feel in our bodies (literally, our veins pulse, stomachs churn, cheeks blush, throats throb, fists clench, eyes leak, etc.). If you’re on auto-pilot day-dream mode, your emotions can be pretty effectively overridden and puppeteered by whatever the great frothing, stress-catering chaos of existence is going to throw at you next. Your mood could be great, then the universe drops a tree on your legs. Ow. You could be feeling awful about your ruined knees, then a lemur jumps into your pocket. What a world. You can wake up on “the right” or “the wrong side of the bed,” or have a sudden, total mood switch instantly triggered by an abstract thought or memory that pop up from nowhere. Feelings happen to us. They often seem to roll in and out of our conscious landscape, colouring the experiences we have like weather. This is a nice and healthy way to imagine them, I think, especially should you need to find some sunny solace in the darkest peaks of winter. Sometimes, feelings simply come and go – patches of cloud and ‘shine – and we need only wait for them to pass.

In other words, then, we don’t seem to be a conductor, directing an orchestra of sensible information and logical instructions to ourselves. We are more like infants, left alone for the day in front of a YouTube playlist for the search term ‘Japan.’

What’s more, this is happening all day.

Indeed, we’re thinking so much, about so much, that we’re basically day-dreaming every moment that we are awake. We are accidentally, unconsciously ignoring the sum worth of The Freakiness, fretting instead on its hundred thousand annoying little mundane components (bills, work, gossip, etc.)

And what are we thinking, exactly? Or, if really want to get into it, why are we thinking at all? Is it really so normal? That sounds kind of weird, but definitely no weirder than it is. When I think, “I want cheese”, who is the intended audience of this information? Well —me— right? But, surely I already know I want cheese, otherwise I wouldn’t think it… right? Or am I the intended audience of this thought? Am I somehow the one being told; the one learning “I want cheese”; the radio receiving the cheesy signal? If so, then, who or what or which process is authoring this thought?

There seems to be an ongoing conversation in our heads, if that’s where we are, yet there’s surely no one in our heads but ourselves to have that conversation with.

III. THOUGHTS

There’s a good, or at least convincing, theory on why we’re talking to ourselves all day, inside our own heads, engaged in a behaviour that would seem outwardly insane if it could be broadcast on loud speakers from our ears to a cafe full of people impressively drinking espressos.

But first, it’s helpful to note that we probably wouldn’t be monologuing to no-one like the mad old Shakespeare of our own minds, if we had not been born in our current, talky-talky modern human context, but instead in the middle of a jungle, estranged from civilisation, raised by a tribe of friendly, mischievous baboons. It should be obvious that in our alternative naughty baboon lives, we would be free of all language-based thought, and our inner worlds would not – could not – be governed by ceaseless linguistic self-chattering, but, perhaps, more by nature’s noise, the leafy sounds of the jungle around us, primal, mystic fears of faceless, shapeless unknowns, and other general baboonery.

Thoughts?

The human civilisation context, however, is uniquely different.

When we are babies, we possess – presumably – some level of consciousness. By which I mean, there is presumably something it is like to be a baby. But conscious is probably just about all we are, so far – indeed, it might just be the purest form of consciousness in some ways, since it is yet untouched, unhurried and undivided by anything so troublesome as an idea, concept, symbol, or bias. No words exist, so no definitions exist to separate anything from anything else. But this state of primordial, pooing-ourselves awareness doesn’t last long, because all the live-long day our parents our blabbering at us; grandparents, too, are making funny, lip-slappy face-noises in our direction; friends, family, strangers, postmen, televisions, radios, all waffling nonsensically in our direction, like mysterious mouth-instruments. We’re encased in an aura of near constant human noise.

Then, after a while, we start to notice patterns in the noise. That meaningless sound –mum– keeps coming up, whenever the creature with boobies that we like so much arrives. Then the meaningless noise –dad– pops up with enough frequency for us to notice that it seems to signal the other one, Mr Useless Bloody No Boobs over there. Before long at all, we’re the fertile soil for a growing vocabulary and grammar, echoing these new sounds back to the world, trying to participate in some mad, desperate attempt to help it understand that we’ve pooed ourselves, or want boobies, or need sleep, or would immediately like for the Red Fire Truck Toy to be in our mouths, please. We want things. We need things. We pick up language, as we would pick up a tool.

All this experimentation, trial and error and copying soon leads us into the world of The Talking; and it’s not long before we’re practising this particularly human brand of communication all day long and everywhere. We become the toddlers, then the young children, wandering around the playground, muttering out loud, monologuing to the world each and every thought that pops in to our heads. Every thought is a word, said out loud, for all to hear. We sound like midget maniacs, but everyone think it’s cute, so we carry on.

big doggy blicenah uhm-na me cup mama go bye-bye he shwahwoooo where doggy where doggy gone? croosh mama doggy bye-bye to the everyday self of Dasein, which is the public they-self.

– Martin Heidegger, age two and a half

Then this out-loud monologuing becomes, well, not so cute. We get older, and older still, and suddenly become increasingly aware that not everyone is just saying everything that they think of immediately, like we are. Adults don’t. Bigger kids don’t either. Our older siblings have stopped. Then our friends – our peer group – stop, one by one, going out like dying stars in a night-sky when something creepy is happening in outer space. The exterior world – and our increasing awareness that we are not free, lone agents, but woven deep into a social fabric that can painfully ostracise us, judge us, tease us, and be mean to us – doesn’t stop our fun, new form of expression entirely, but cautiously pushes our monologuing inwards, to the only place left where it is socially safe from the dangers of the tribe: our consciousness.

The voices of mum and dad, which became our broadcast-out-loud playground voices, become the voices in our heads… where they will stay forevermore, bickering and dictating the moment-by-moment account of our lives, memories and imagination on our own private radio station, Head FM.

And what’s more – we forget this process happened. The day-dream begins.

We can no longer see the voice in our head as a detached and different entity, as it once was, falling from the mouths of others. No, now we identify with it. Suddenly, the voices in our heads stop being just those –voices–in–our–heads – coming in and out, automatically. Instead, they become us. It becomes me. The innocent thought rolls in, “I want cheese,” and suddenly that baby – that free, agenda-less baby absorbing its environment as a pure, unified field of conscious experience – is a cheese-chasing self, deciding itself for the first time as separate to everything else. The baby’s identification with the voice has, clumsily, inadvertently, spawned an ego. Oh dear.

Those that fail in this process – who don’t internalise the voices – become the unsettling people of our world; the muttering, monologuing madfolk we see “talking to themselves” – just as we are – except they’re not following the Unwritten Rules of the Civilisation. They’re Talking to Themselves wrong. We’re doing it right, though, aren’t we? “Yes,” say our egos, those strange and delicate creatures in charge of all of us and everything. “We’re doing it inside our heads, just like we’re supposed to,” we whisper to ourselves.

IV. THE THEATRE

So there is consciousness – the theatre – and thoughts and feelings – the actors and the orchestra – which play out upon its stage. And there is the full, immersive experience of reality, which you can most easily notice when you try to locate your head, and fail.

And this nothing where your head should be is, well, as the man on the night-bus would say, everything. It’s where the magic happens.

When we close our eyes and put our fingers in our ears, and shut up, it is easy to notice that, behind the input of our sight, behind the input of our hearing, behind the inputs of all our other senses, there is something left. Or, to put it another way: even if you applied a blind-fold, two ear-plugs, local anaesthetic to your whole body, and then floated in an isolation tank until you were not aware of the weight, position or even the sense of having a body, there would not be nothing. Obviously. ‘You’ won’t be gone. Nullify all of your senses, and you won’t nullify the presence of which they are the probing tentacles, groping the external world around you, like the many hands of a reality pervert. Feel free to take a few minutes if you want to confirm this for yourself.

Doo be doo be doo.

Did you? Of course not, you naughty reader.

What this something is, though, remains fundamentally mysterious, and it’s weird that something so fundamental is so mysterious, because, at the same time, this something has the equally weird quality of feeling – subjectively, and with typical human arrogance – like it is the centre of everything – the point at which all things in existence seem to simultaneously begin and end: you.

When we close our eyes, it is easier to be aware that this something, is, kind of, sort of, a bit, well, like a space, and we can further notice too that it doesn’t seem to have any limits, or boundaries, or corners, or edges, or anything that something inside a head – if that’s where it is – should have. And this too is capital letter Weird. Isn’t our head 20cm by 18cm by 13cm, with a 56cm circumference? Wikipedia says so. Isn’t it bone, and gristle, and skin, and brain, and blood, and hair, and a cute, boyish face? My creepy doctor says so.

So, what right does this meat bloody football on my meat bloody neck have containing an infinite bloody space?

![[10] Guy](http://www.hencewise.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/10guy_2.png)

(Not to scale.)

Generally, Russell Brand sounds most like a person you shouldn’t listen to when he’s talking about “god,” but if you ever probe into what he means by “god,” and I did, you don’t actually get a presumptuous and all too familiar account of an exterior rumoured (male) sky personality – the character ‘God’ whose name people shout before they blow themselves up in crowds – but simply this:

What [religions] are trying to do is make sense of our perspective as awake, conscious, sentient beings within the infinite. For me, as a person who believes in god, my understanding of god is this: My consciousness emanates from a perspective, and it passes through endless filters – the subjective filters of the senses – and of my own biography (“this is good, this is bad, this is wrong, I want this, I don’t want that”) – but behind all of that is an awake-ness; an awareness that sees it all […] None of us can know if there is a god, but we can know there is an us.

In other words, he’s not – as it might first seem – endorsing a judging, watching, needy and suspiciously human-like deity that certain things must be done to appease, but what instead amounts to a different, more Eastern, notion of consciousness (god is not ‘out there‘, but ‘in here‘.) At best, Brand’s philosophy is a nice, innocent means of connecting with the profoundness of existence, and, at worst, little more than a fluffy logic circle, that could instead read: “None of us can know there is a god. We can know there is an us. My consciousness emanates from a perspective. I’ve just decided to call this consciousness “god,” to confuse everyone.”

In other words, Rene Descartes’ (who is not a woman at all, it turns out) famous, 400-year-old one-liner, ‘I think, therefore I am.’

We can see, anyway, that some people are using the words consciousness and god, almost interchangeably. Indeed, in light of admitting what we don’t know, all of the tricky words at the beginning of this article start to seem like nothing more than synonyms for consciousness: It’s where reality is happening; It is the something made of nothing; It is the subjective, in which the objective occurs; the no-thing in which all things appear; Having it is existence; Not having it is non-existence (or, as the cool kids sometimes call it, death); If the Big Bang was a tree falling in the woods of infinity, we beings of higher consciousness are the witnesses in the dark cold silent emptiness that know it made a sound.

As Carl Sagan – astronomer, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, and stoner – once said, presumably in an alarming whisper to a fellow passenger at 3am:

We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.

V. THE HARD PROBLEM

It’s easy to see – when confronted with the full Weirdness of what’s going on – that almost everyone on earth, especially every particularly religious maniac, is grappling with, and arguing over, a different flavour of the same original controversy; and almost all viewpoints, and even ideologies, are stemming from the same source presupposition that we don’t at all understand, however much some philosophers, theologians, gurus, priests, spiritualists, and 4am drug-addled loonies in a drum circle might claim to. Or, to put it a simpler way:

If you think you know what the hell is going on, you’re probably full of shit.— Robert Anton Wilson

What’s more, science (those guys) is uncharacteristically quiet on the subject, because the Scientific Method can only probe the ‘objective’ reality that we all (seem to) share, but has no means or measurements which apply to the ‘subjective’ realm of qualia and experience. We can see blood activity in brain scans and we can ask for the subjective feedback of a human adult subject, but we can not make an experiment which sheds light on what it is like to see colours, think like your partner, or be Mel Gibson (luckily).

In other words, while science, maths, and language seem to point towards the common-sense, Occam’s razor conclusion that we are all sharing an objective world, we are all experiencing all of this objectivity, subjectively. We all live on the same planet, I hope, but we see it through 7 billion+ separate, subjective lens. This is the final veil that we can not peek behind. It is the inbuilt limit to the kind of understanding we would like to have of the world, because we can not find a better position to observe the back of our own heads, no matter how hard we pull on our ponytails.

We call this absolutely massive nightmare, rather cutely, The Hard Problem of Consciousness.

Understanding the depth of the riddle that consciousness poses is to understand much about the world, because it is the space in which religions, cults, spiritual mumbo-jumbo, looney ideologies, and other faith-based systems can operate. It is the blind spot of science, and the weakest link in all of our collective ideas about the world – because science is only a methodology for testing truth claims, which is what makes it so remarkably effective at dissecting, labelling and predicting the mechanistic, materialistic, and physical laws of our universe, yet why it can shed little of worth on the rather inconvenient fact that at the base of every experiment, theory and conclusion about our ‘objective’ reality, there is an inevitably subjective second layer, with simply no conceivable way to penetrate it from a place outside of ourselves.

This should be the source of our sympathy with non-harmful, faith-based beliefs: that all of the religious people born in Salt Lake City, Utah, or Belfast, Northern Ireland, or Dabbiq, Syria, are born with an infinite fucking hole in their sirloin steak heads, where Nothing and Everything seem less like the opposites they’re supposed to, but more like equal sides of the same ancient mystery. As the absurdist writer Alfred Jarry joked out loud, just before the passenger next to him suddenly decided to walk home three stops early:

God is the shortest distance between zero and infinity.

Now, I personally don’t consider myself spiritual or religious, but I’m certainly obsessed and confused on a day-to-day basis with the fact that I am a Consciousness – and I live my life, as much as I can or remember to, marvelling at and cherishing the mind-bendingly weird, wondrous and impermanent nature of this experience I call ‘me’. Indeed, ‘consciousness’ is just about the one thing – as a science-nerd and woo-woo-skeptic – I’m willing to happily apply the word ‘magic’ to. It’s magic to be conscious. There, Richard Dawkins, I’ve said it. Life is – or can be – a merry-go-round playground in fucking Narnia. We are not just alive, like grass – we are magic unicorn creatures, frolicking around in a literal Garden of Eden gravity-dent in space-time, witness to some amazing tangible dream of a reality where nothing and everything seem so suspiciously interrelated we have to invent words like GOD just to fill the gaps where no other words will go.

Woah.

VI. THE LENS

“Is”, “is.” “is”—the idiocy of the word haunts me. If it were abolished, human thought might begin to make sense. I don’t know what anything “is”; I only know how it seems to me at this moment.– Robert Anton Wilson

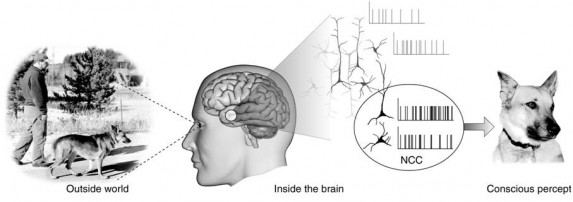

The way I like to think about consciousness is this: there is seems to be an objective world – the one we all share, and poke under microscopes – and a subjective world – the private one we tend to believe is between our ears, neck and hat. More importantly for our purposes, though, there seems to be something inbetween these two realms of thing: our selves – i.e. our thoughts, feelings, and personalities – or, in totality, our subjective perception of the objective world. It feels like we are in the middle; the overlap in a Venn diagram of reality. What we perceive, feel, think, remember, understand, believe, have faith in, even what we don’t know, is the lens through which one passes into the other; the funnel through which the universe pours into us. Here is a diagram, which contains a cheeky bit of science:

Look, in the middle… science!

And our ‘perception’ – luckily – is something that is seems to be a great deal inside our control, in the easy to comprehend ‘glass half-empty, glass half-full’ sense, (whether we have Free Will or not). This is probably the greatest blessing of the human mind: it has (or can have) power over itself. We can learn new ways to think about things; we can improve the ways we think about things; we can think better, smarter, healthier, happier, wiser, and there’s absolutely no good reason why we wouldn’t be able to. The play in the theatre might be the same, but we can watch it from a ten thousand different seats.

In other words, our experience of the universe is programmable, because – subjectively – we are all riding around in our own customisable personal universes of one. We possess then the only tool we need to hack reality, as reality appears to us. The world is a gym that our minds can get fit in. (Yuck!)

VII. HACK REALITY

The voices in our heads can be healthy, or at least healthier, and it’s plainly obvious that some people’s minds are stuck in horrible old habitual patterns, completely unexamined, broken since childhood, badly configured to process the raw data of living, blocked off to any possibilities of self-improvement, operating instead like finely-tuned instruments that have been calibrated only to annoy themselves.

If these sorts of people could be persuaded to point their attention ‘inwards’ occasionally (yuck), they could perhaps learn to recognise this, or disassociate themselves from the automaticity of their more unhelpful thoughts, and thereby create a space for themselves to have new, different, healthier reactions. This harmless little idea was the great revolution in psychiatry that birthed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), the basic premise of which is to train practitioners to notice when a habitual thought pops up like ‘I need a drink’ or ‘I’m such a shithead,’ and then think, ‘oh, look, there’s that unhelpful thought again, right on time. Ha, silly-mind-voice that I’m not in control of.’ CBT – available on all good health services now – actually has a lot in common with mindfulness, which is probably the closest English word to the Buddhist idea of Vipassana (‘Insight’) meditation, which is probably the closest Tibetan idea to occasionally listening to the incessant jabbering going on inside your mad fucking head.

Oh, hi. At this point, having just prescribed meditation to you and everybody, I should probably confess something: I still don’t actually meditate. Sorry. However, the important thing to know here is that I used to not meditate in the same way that I used to not do homeopathy, aromatherapy, and crystal healing. Now, though, I don’t meditate in the same way that I don’t eat more vegetables, jog, or get up early, which is better.

I’m very wise.

Luckily, though, I think it’s even possible for hopeless slobs like me to steal some of the low-hanging fruits of meditation, just by understanding what it is, what’s it for, and why one might choose to do it at all. If you were at all like me, imagining meditation as little more than a relaxation technique for boring people, you might have missed roughly the whole point of it being a readily available mode of attention. You don’t have to be cross-legged, closed-eyed, humming ‘om’ in a forest, and not vaccinating your children. You are instead quite free to ‘meditate’ – i.e. notice the incessant jabbering – whilst you do all kinds of normal, unenlightened person things, like walking down the street, cooking an egg, or gawping at a smart phone as you wander into traffic.

I plan to start, the way I plan to start lots of things (please note: no guarantee I’ll start.) The method will be, I think, to start with an amount of time so low that it is impossible to fail, then adding tiny, tiny amounts of time each day, until I eventually reach a point that – without even really trying – I am no longer a hypocrite.

VIII. YOU

There is only one corner of the universe you can be certain of improving, and that’s your own self.– Aldous Huxley

If we realise that our experience of reality is all we have/are, this realisation – and more importantly, the intentional practice of noticing/utilising it – bestows us with great power over our lives. We can be responsible – to a large degree – for our own happiness, and for overcoming our own problems. Of course, some harder to mediate chemical and physical processes will always be running parallel in our hardware (endorphins, serotonin, dopamine, oxytocin, adrenaline, cortisone, etc.), but we can nevertheless do a lot for ourselves by consciously choosing to upgrade the Operating System of our ideas, thoughts and world-view with a myriad of software. Common tools for self-improvement include philosophy, drugs, meditation, therapy, nutrition, exercise, art, travel, self-help, Stoicism, cold showers, and ignoring Donald Trump until he goes away.

If our ‘happiness’ and our ‘sadness’ are taking part ‘in our heads’, if they are products of our thought processes, if they are directly interrelated with our beliefs, then it seems entirely logical and sensible to say that changing the way we perceive the world – and here comes another classic half profound/half inane soundbyte for your collection — can often be as good as changing the world.

If your brain is operating on the irrational Belief System of racism, for example, you can upgrade it, and instantly find that the same world you’ve always been in is suddenly a lot more full of friends. If your brain is operating on the irrational Belief System of unconsciously, unthinkingly plodding through life on un-choosing inertia, you can upgrade it, and instantly find that the same world you’ve always been in is suddenly a very elastic realm of near-infinite capacity for change, quite ready to accommodate and absorb any new and different life you might prefer to live in it.

You can choose not to be the victim of your own biography.

You can choose whole new characters to play in this drama.

The “rest of your life” – the only bit worth worrying about – begins, always, now.

This is the hippy dream and the New Age mantra – that the world is what we make it. Yet due to our discovery and increasing understanding of neuroplasticity (the brain’s structure is not static, but remains flexible long past childhood), and neuroscientists’ increasingly clever use of fMRI machines as a scientific tool, there’s promising evidence – although it’s early days – to support claims that healthy habits and beliefs might actually be having corresponding good physical effects on the brain itself (1 / 2 / 3). It certainly doesn’t seem naïve or controversial to believe this, or the implications of it, especially in the subjective light of inspecting our own consciousness and identifying its character as the pivot upon which our whole lives balance.

Every new fMRI machine now comes with a monk

If our thoughts and feelings have the tendency to come and go, automatically, apparently beyond our conscious control, abstractly overlaid on the cinema experience of our own personal realities, then this endless show of private words, images, emotions and concepts in our inner lives has the potential to drag us along on all kinds of bizarre and convincing agendas (ISIS), unless we’re occasionally checking up on them like a nosey parent at a locked teenager’s door. What’s more, it’s actually this unconscious mechanism of thinking–whilst–not–noticing–that–we–are–thinking that is the main barrier to ‘connecting with’ (noticing) the profound reality of the endless, flowing ‘present moment’ we find ourselves wrapped in.

It is always now. This might sound trite, but it is the truth. It’s not quite true as a matter of neurology, because our minds are built upon layers of inputs whose timing we know must be different. But it is true as a matter of conscious experience. The reality of your life is always now. And to realize this, we will see, is liberating. In fact, I think there is nothing more important to understand if you want to be happy in this world. But we spend most of our lives forgetting this truth—overlooking it, fleeing it, repudiating it. And the horror is that we succeed. We manage to avoid being happy while struggling to become happy, fulfilling one desire after the next, banishing our fears, grasping at pleasure, recoiling from pain—and thinking, interminably, about how best to keep the whole works up and running.― Sam Harris

How can we become happy – the great goal of the thinking Earthling – if we are entirely at the mercy of our thoughts and feelings, distracted at all times from perhaps the one and only great “spiritual truth” there is to be known or found in our universe: that is, the plain, old, normal, everyday, ordinary fact of finding oneself awake in a universe at all.

Well, the wiser people of our world argue mostly that we can’t. We can grasp madly at pleasure (drugs, shopping, cake), and flee madly from displeasure (feelings, exercise, death), but we cannot make progress towards any more sustainable goal, if we’re just going to be hedonistic pussies about it. If some brand of happiness, contentment or elevated self-worth is really our project in this world, and its hard to think of a better one, we cannot remain cut adrift in our lives, with our emotions dictated by the chaotic whims of a vastly unknowable exterior environment, and our thoughts frothing up from some infinite, unknowable well of internal insanity. No thanks, life.

We could instead peek into this inner realm, in which our lives are happening. We might just find the general amazingness of our lives is only lightly hidden, just past the regularly distracting normalness of them.

Further Reading:

What, you want more words? You lunatic! OK, then, but you won’t get anything done today…

The Headless Way – a website of quick, 5-second ‘experiments’ that even idiots can use to notice profound things about themselves.

Mindfulness in Plain English – a well-written, simple and refreshingly bullshit-free “how to” style book about meditation, if the idea of trying it tickles your pickle.

Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion by Sam Harris – a great book on the topic of consciousness/meditation by a neuroscientist, philosopher, and famously nonsense-phobic atheist.